Deadlocks: the dark side of concurrency

This is a transcript of a talk I gave at Gophercon UK on 2021-10-25. You can watch it on YouTube (47 minutes) or see the slides and read the words here.

Go makes it so easy to write concurrent programs that sooner or later you will run into a deadlock. A deadlock is where your program (or part of it) just stops working for mysterious reasons.

This talk will explain what deadlocks are and why the Go deadlock detector isn't very useful in real world programs.

Deadlocks can be very difficult to find and fix and this talk will give lots of tips on how to figure out why your program deadlocked and how to fix it and avoid deadlocks in the future.

You will need an understanding of go routines, locking (sync.Mutex) and channels to get the most out of this talk. No previous deadlock experience required!

Introduction

Hello and welcome everyone.

I’m Nick Craig-Wood and I’m going to be talking to you about deadlocks.

This is an intermediate level talk, so I’m assuming you know what a go routine is and have some idea what a channel and a mutex is.

I’ve put a link to the code samples up there – you don’t need them as I’ll be putting them on the screen, but you can have them for reference during the talk or later.

In this talk we are going to talk about what a deadlock is, how to debug them and how to avoid them in future.

It will have lots of real world examples culled from dozens of painful examples in the rclone codebase!

I learned about deadlocks the hard way by having to debug lots of them and I’m aiming of for this to be the talk I would have like to listened to when I knew nothing.

Hopefully everyone, no matter how experienced will pick up a few tips.

But first a little bit about me. At the moment I’m mostly doing Open Source coding on rclone with a bit of consultancy.

I’ve been using Go for 9 years since before version 1.0. I got into it when I was a busy CTO and found I was doing nearly 100% people management and strategy with no time for coding. So I decided I’d learn Go in my spare time because it sounded interesting and I needed a programming activity to keep me sane.

After writing a few small things in Go, I started started the rclone project in 2012 and its been growing ever since, now with 30 thousand stars on GitHub and millions of downloads a month.

That’s been quite a ride but I’ll save that story for a different talk!

Since all the real world examples in this talk come from rclone I’ll tell you a little bit about it.

Rclone is a highly concurrent command line tool to sync your data to and from any cloud storage system. It supports over 40 providers including s3, dropbox, google drive, azure and lots more.

It tries to do everything it can to maximise your network and disk bandwidth and minimise the chance of data corruption.

It can also mount your cloud storage system as a network drive using its FUSE filing system.

To make it run fast rclone is riddled with Go routines, and the inevitable channels and locks which go with them and in turn the inevitable deadlocks.

Before I started on the rclone journey I knew nothing about deadlocks!

What is a deadlock?

So what is a deadlock?

Here is Wikipedia’s rather abstract definition of a deadlock – something to do with one process holding something another process needs.

I prefer to think of them as a catch 22 situation.

Rather like a newly graduated developer: you need experience to get a job, but you can’t get experience until you get a job.

In a deadlock the other process has something you want, and you have something the other process wants and you are both prepared to sit there and block forever until the other process gives you what you need.

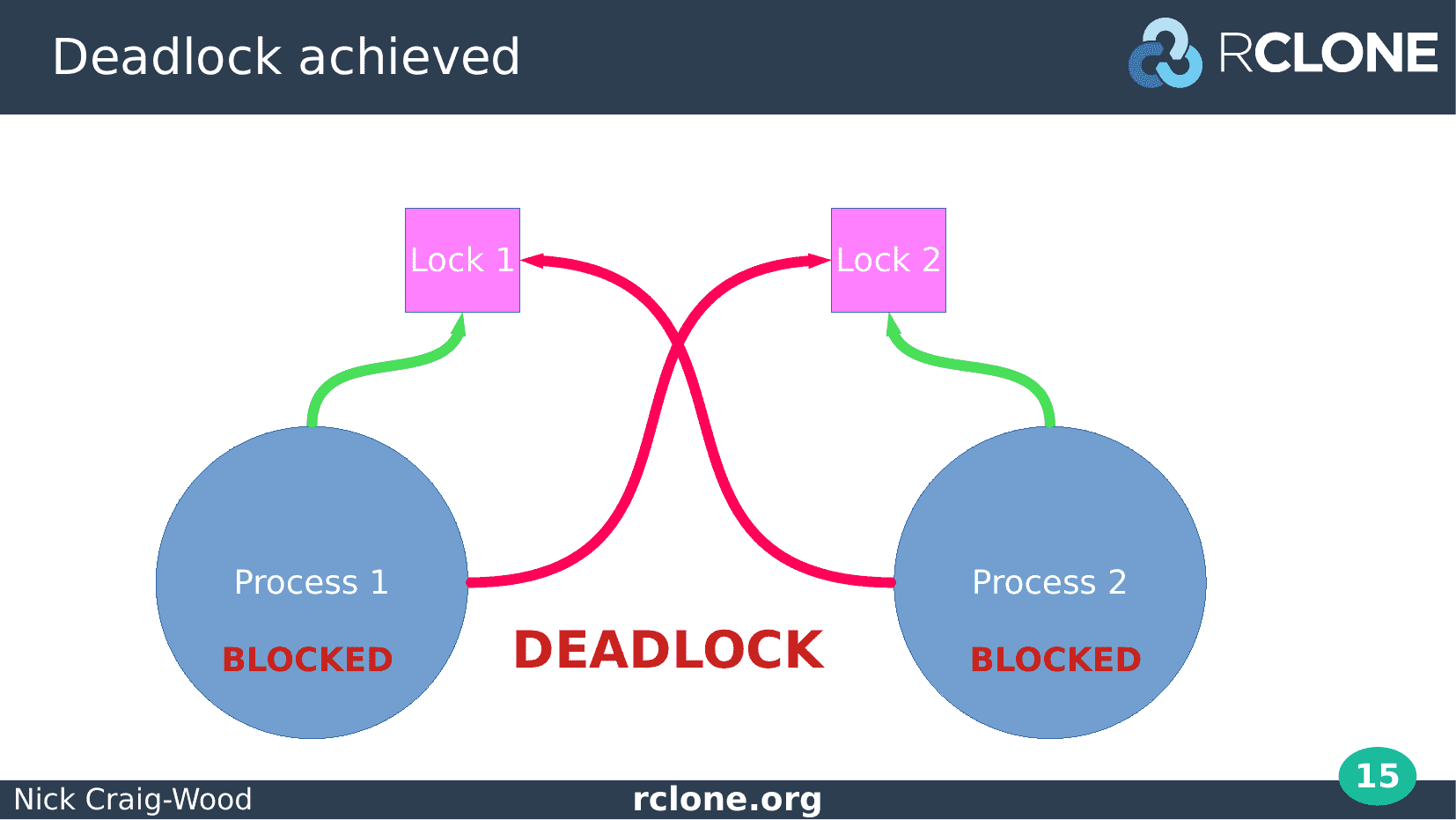

Let’s go through a deadlock in diagram form.

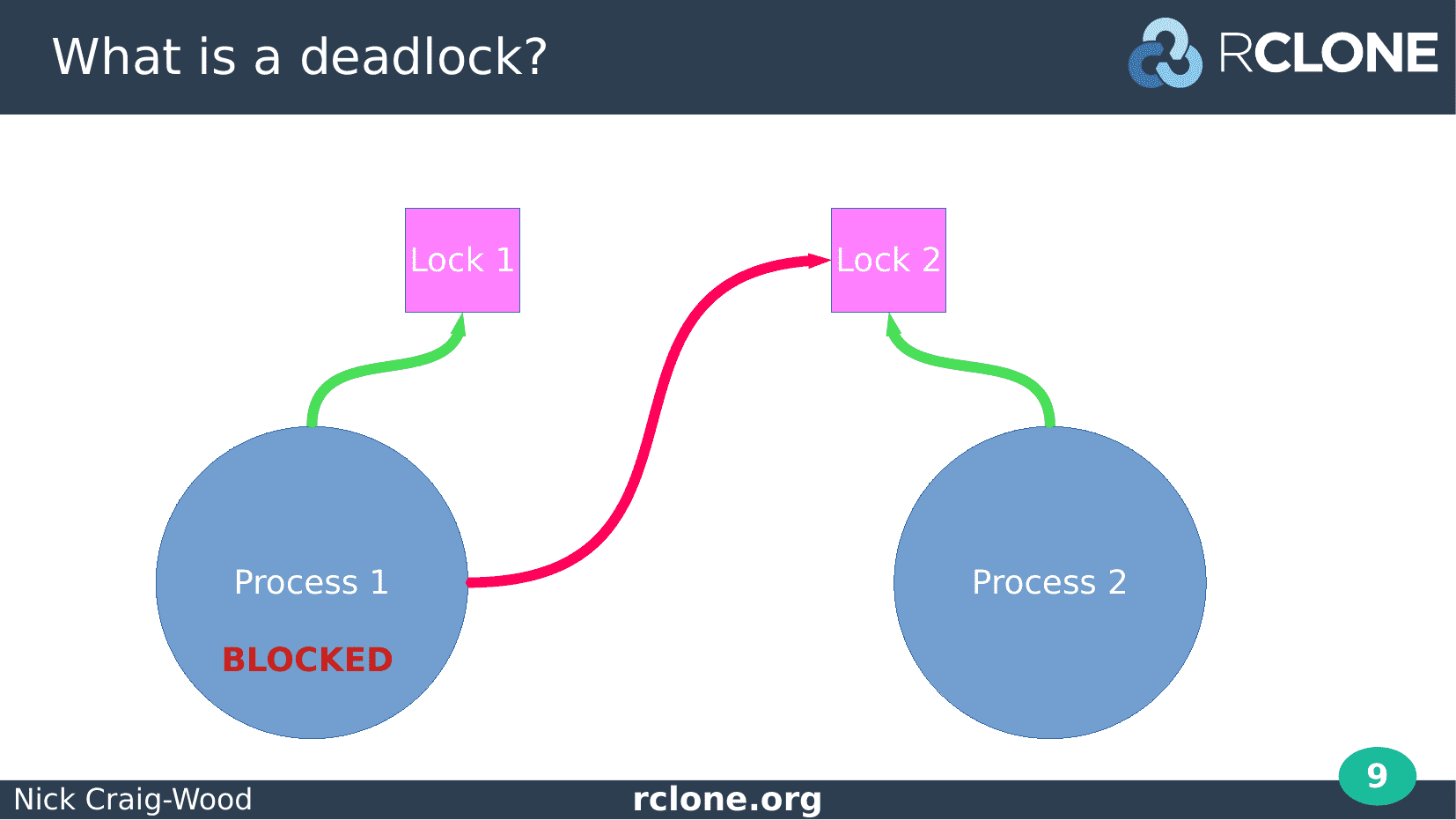

Here we have two go routines (the blue circles labelled Process 1 and Process 2) and two locks (the pink squares).

Each lock could be a sync.Mutex or a Read Write Mutex or maybe even a write to a channel.

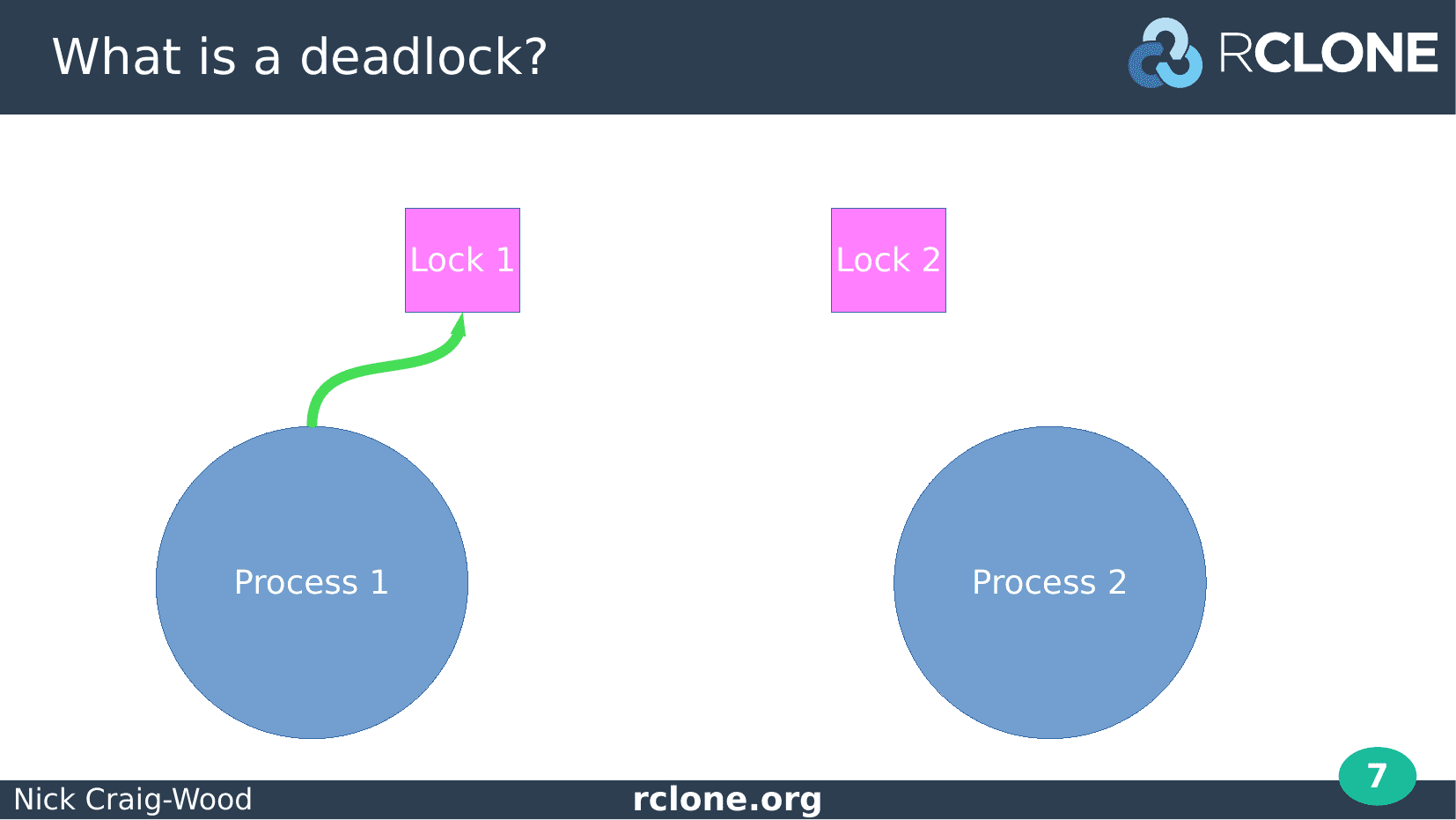

The first step is Process 1 takes Lock 1. All good so far.

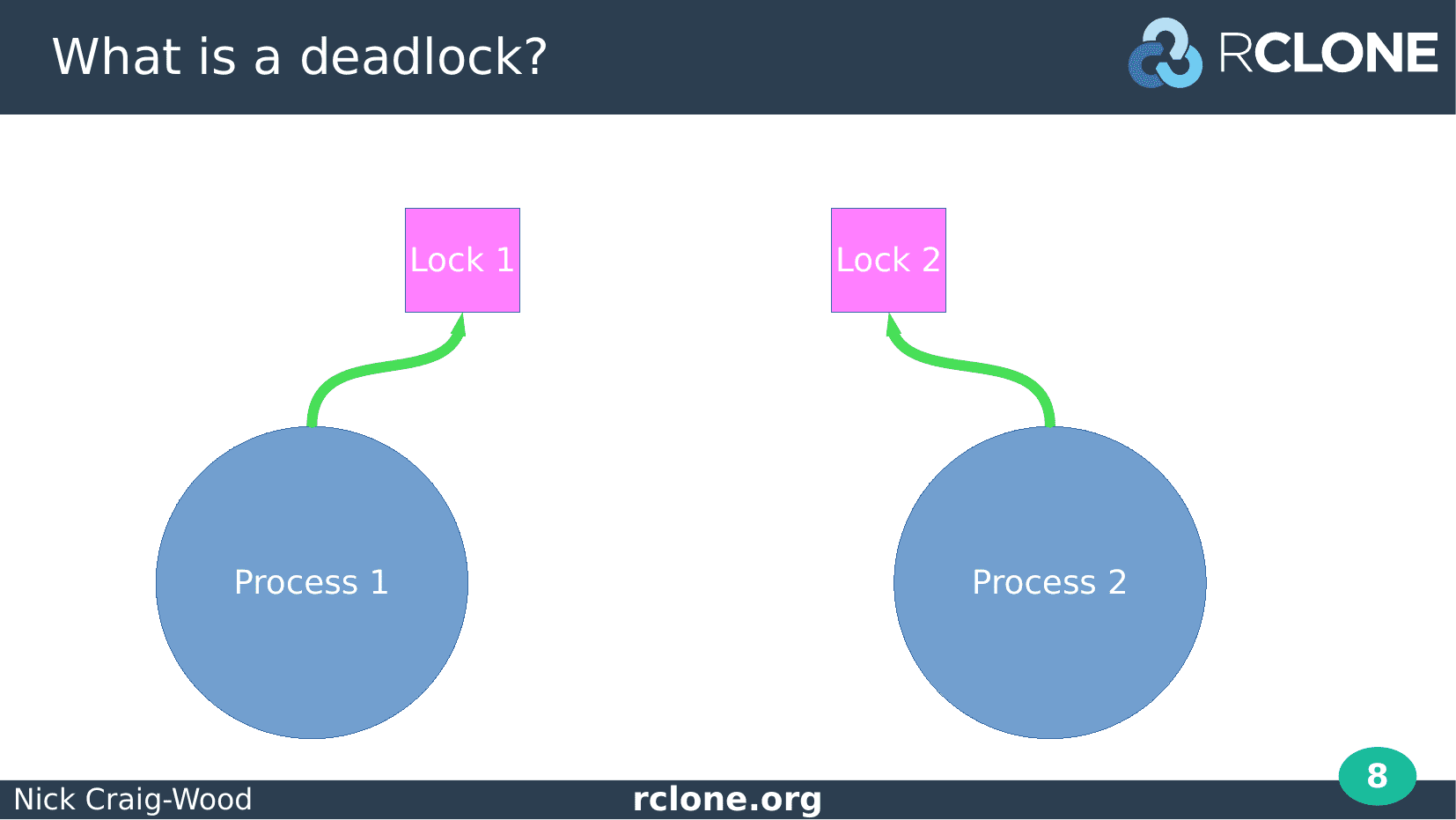

Next step is process 2 takes lock 2. Again all good, nothing to see here.

Now process 1 attempts to takes lock 2. This causes Process 1 to block and wait for lock 2 to be released as lock 2 is already taken by process 2.

We haven’t reached deadlock yet as everything could be resolved as soon as Process 2 drops Lock 2.

However it doesn’t do that...

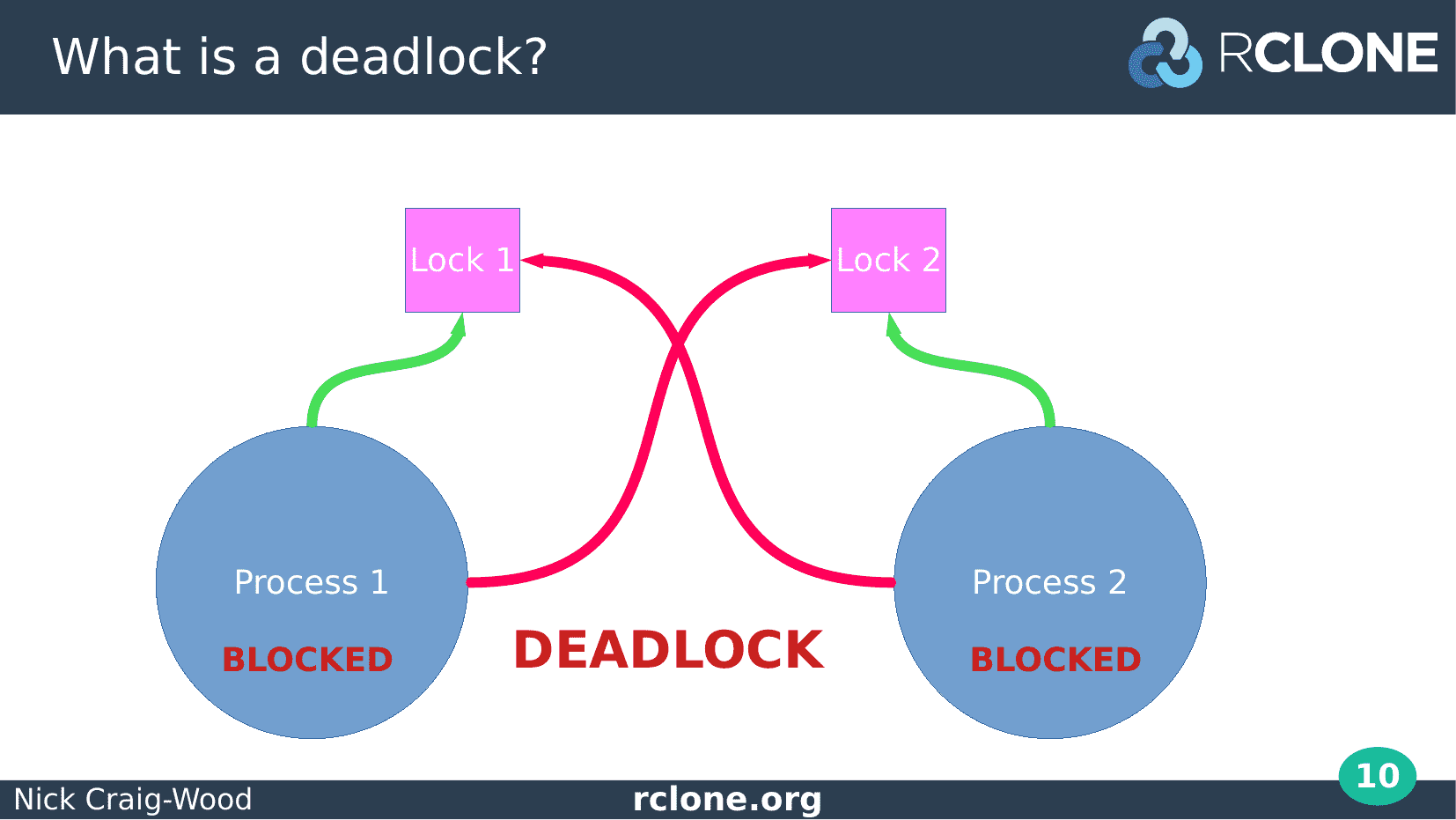

Process 2 now tries to take Lock 1.

This is unsuccessful because Lock 1 is taken by Process 1 so Process 2 blocks waiting for it to be released.

Now Process 1 and Process 2 are blocked. They will never proceed as each is waiting for the other to release a lock.

These two processes are now deadlocked.

This means that some part of your program has stopped working and will never work again.

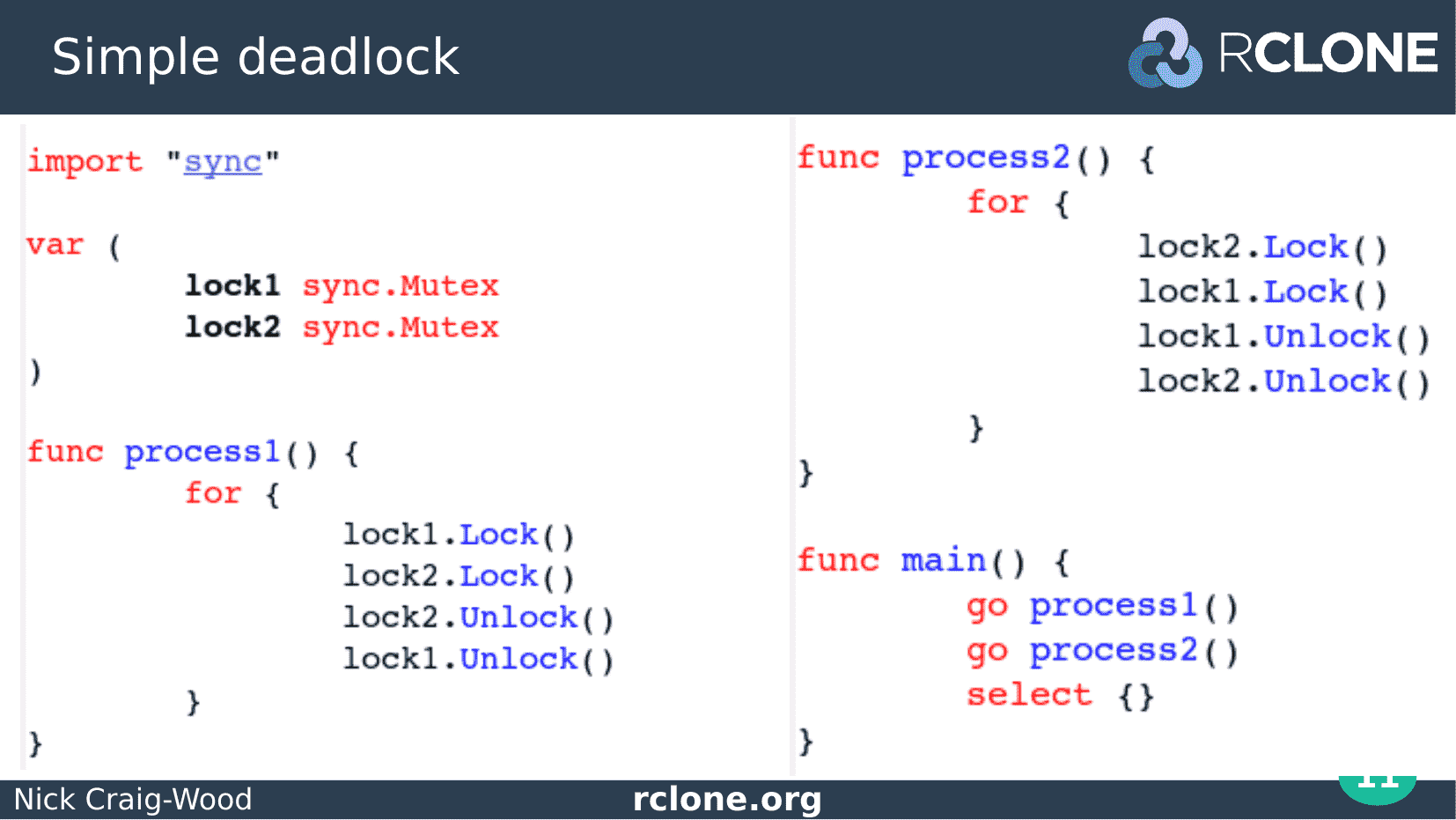

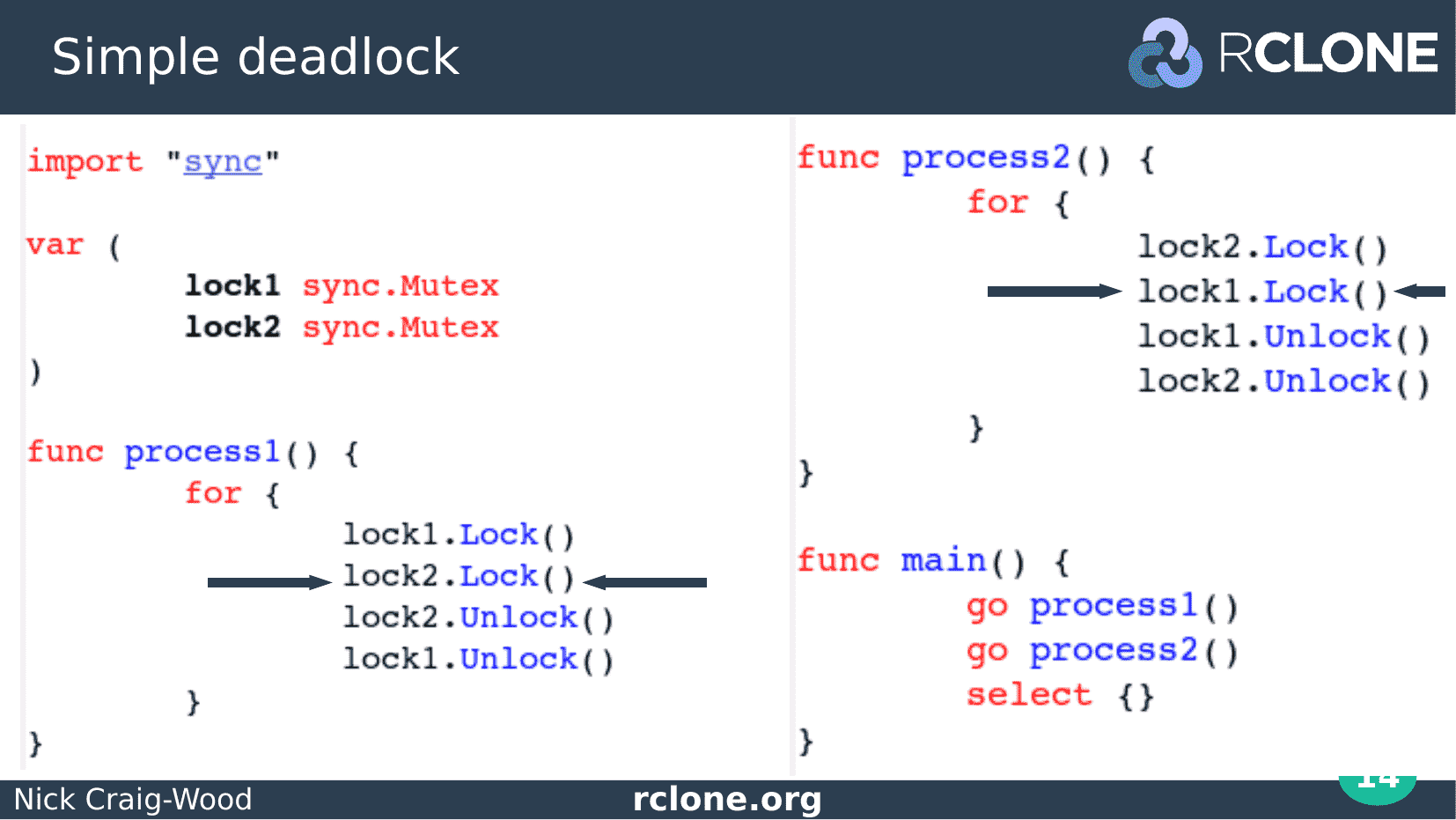

Let’s see what that might look like in Go with a simple bit of code.

We have process 1 and process 2 just like in the previous example and they are going to sit there in a loop, taking and releasing lock1 and lock2.

The only difference between process1 and process2 is that they take and release the locks in a different order.

This code looks like it should work, but it will deadlock pretty soon.

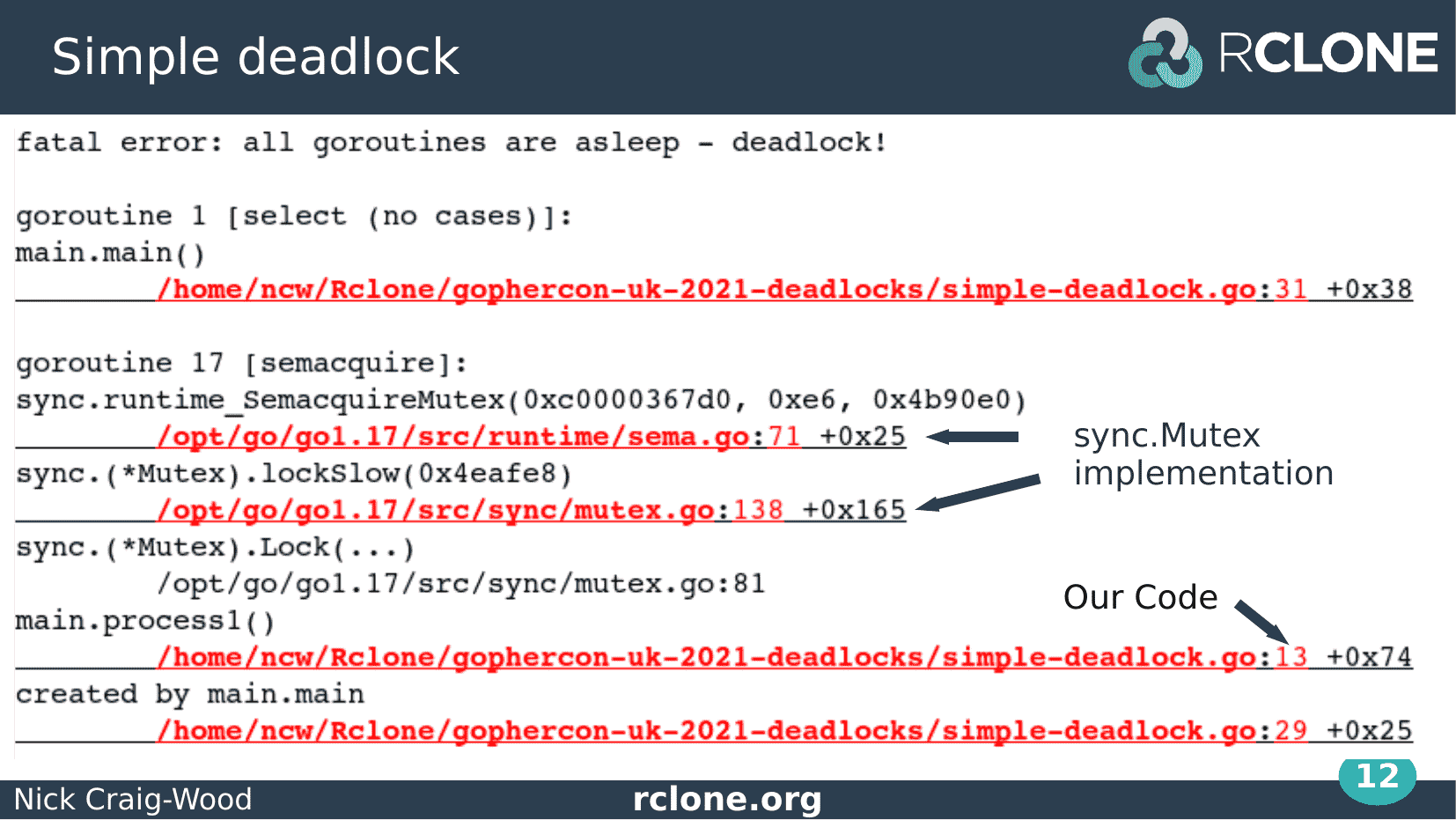

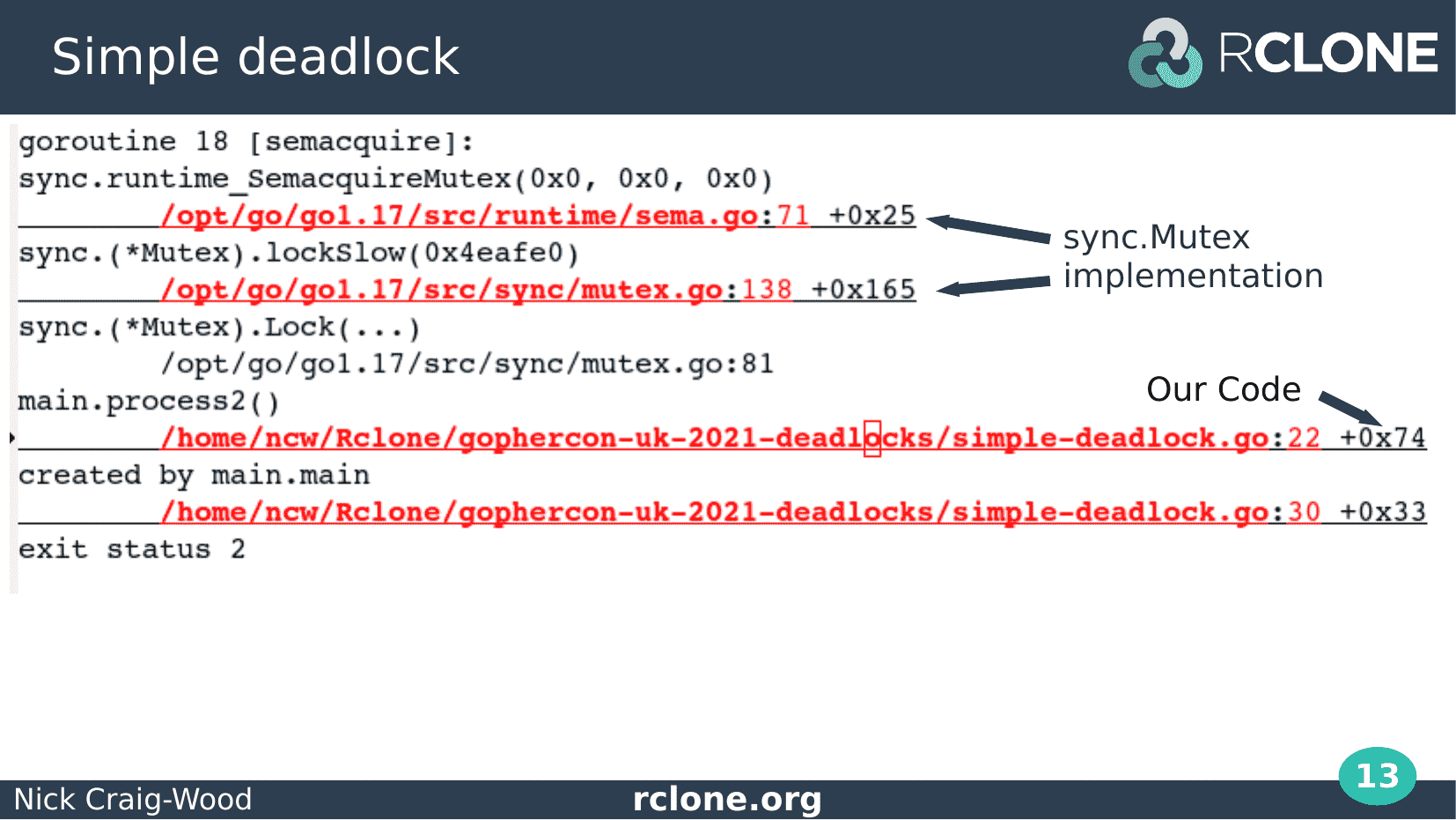

This is the output once you run the code.

First thing to notice is that the Go runtime has detected the deadlock giving the nice friendly message “all go routines are asleep – deadlock”.

The runtime gives a backtrace of all the Go routines that are running which is very useful for working out what went wrong.

The disadvantage of this is that they can be very long – even this tiny example needed 2 slides to fit it on.

Go routine 1 is waiting on the select with no cases that we put in to stop the program ending too soon. We can ignore that.

Goroutine 17 is in state semacquire – its deadlocked calling the sync Mutex implementation.

Here is the next bit of the output.

In goroutine 19 you can see a different bit of our code in also calling the sync Mutex implementation. Again it is deadlocked in the semacquire state.

I’ve put arrows at the bits of code that the backtrace indicates the go routines are executing.

You can see process1 has taken lock1 and is blocked taking lock2, whereas process 2 has taken lock2 and is blocked taking lock1.

This is a clear deadlock. Whenever you see a trace where a single go routine takes more than one lock, you should be thinking about deadlocks.

This is exactly what we expected from our initial diagram, process 1 is blocked taking lock 2 and process 2 is blocked taking lock 1.

It is nice to see theory and practice agreeing!.

You’ll have noticed that Go can detect deadlocks.

This is very useful, but unfortunately it very rarely detects deadlocks in actual code.

This is because all the Go routines in your entire program have to be asleep for it to trigger and in my experience that almost never happens except in toy examples like these.

There is always something else going on, like log collection or statistics calculations or something like that which means the race detector does not fire.

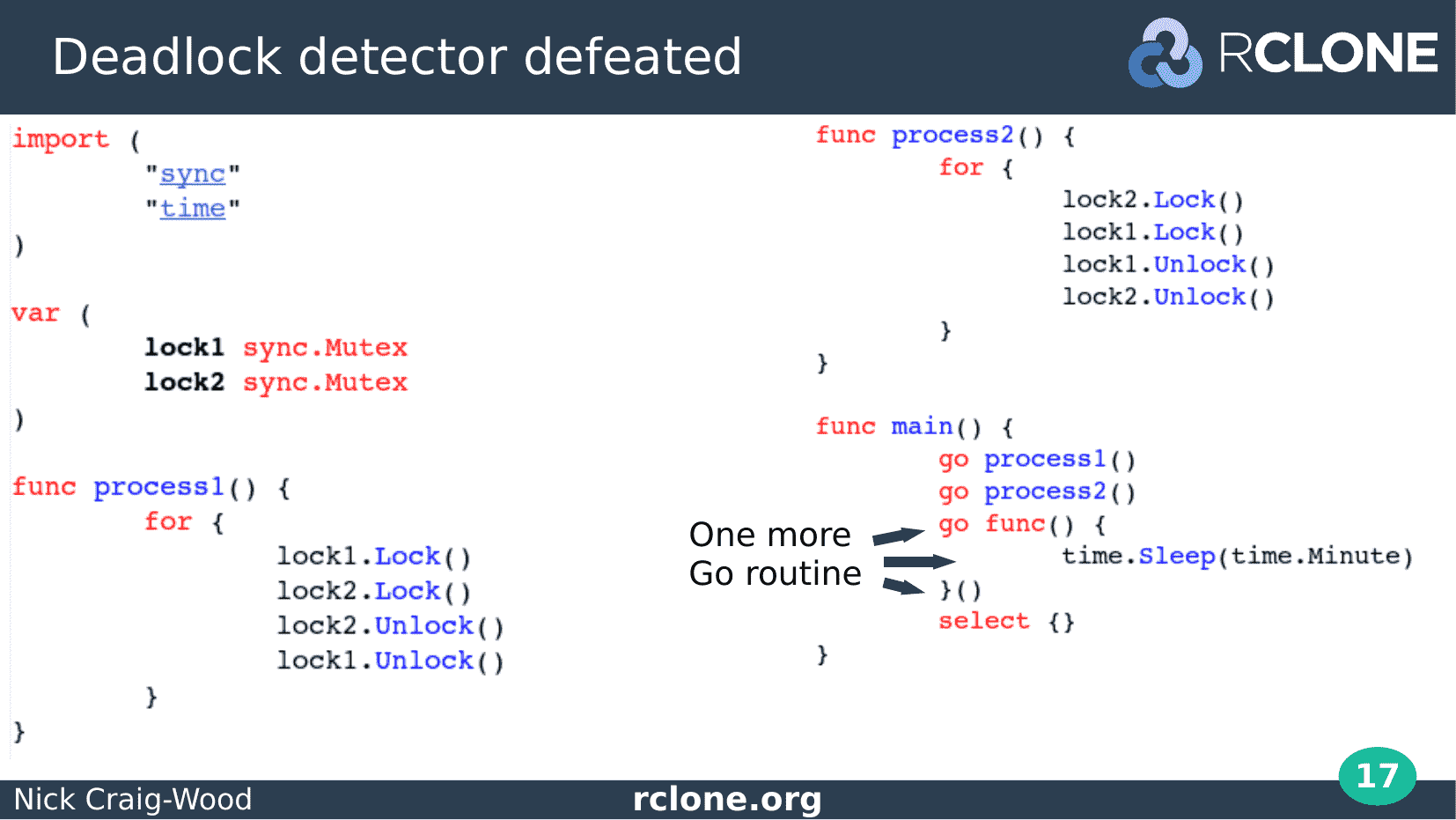

This time if we add one extra go routine as indicated the deadlock detector does not kick in, and the program deadlocks silently.

Or rather part of the program - process 1 and process 2 - is deadlocked but the rest of it is working fine.

Unfortunately this is the usual state of affairs when debugging deadlocks – some part of your code just stops working with no other symptoms.

Enough of your code may be working to give you the idea its it isn’t broken but some important part isn’t progressing.

We’ll see in the next section of the talk what to do at this point.

A quick diversion, as I expect this question has popped into your minds already.

Can we use channels instead of those nasty Mutexes to avoid deadlocks?

Alas, no, you can cause a deadlock with channels just as easily as with Mutexes and we’ll see an example of that later.

In my my experience with rclone only about 10% of the deadlocks are with channels so they are less likely certainly.

So why do we get deadlocks?

There are two ingredients.

The first is concurrency. Without concurrency, that is things happening at the same time, we can’t have deadlocks.

This means that single threaded code can’t have deadlocks which is a point we’ll come back to later.

The next magic ingredient for deadlocks is locking.

When I say Locking here I’m including channels. Reading and writing to channels can block your program just as easily as Mutexes.

And if I wanted to be really precise I’d say shared resource acquisition instead of Locking because you can get deadlocks using other things other than Mutexes and channels, for example using file system locks.

So where did these locks come from?

My excuse is the race detector made me do it :-)

So what do we do to pacify the race detector? We put locking in, and sooner or later once you’ve put enough locking in you will cause a deadlock.

I’m joking here of course, the go race detector is wonderful.

It tells us about data races which would have caused silent corruption in our programs.

Let’s just sing the virtues of the race detector for a moment. It is a technological marvel and very close to magic.

The race detector will tell you when your program runs a risk of memory corruption due to unsafe accesses.

If you are writing concurrent programs you should run your tests with the race detector, and if you can, some of your production binaries too.

Any problems it finds are always real problems – I’ve never known it make a mistake.

However when fixing the things the race detector points out, do think about what deadlocks you are about to create.

In particular think about what locks might be already held and what locks you might want to take in this go routine.

How to debug a deadlock

Here is an example I’m going to use quite a few times.

It is a simplified example from rclone’s FUSE based filing system for mounting remote cloud storage as if it were a local disk.

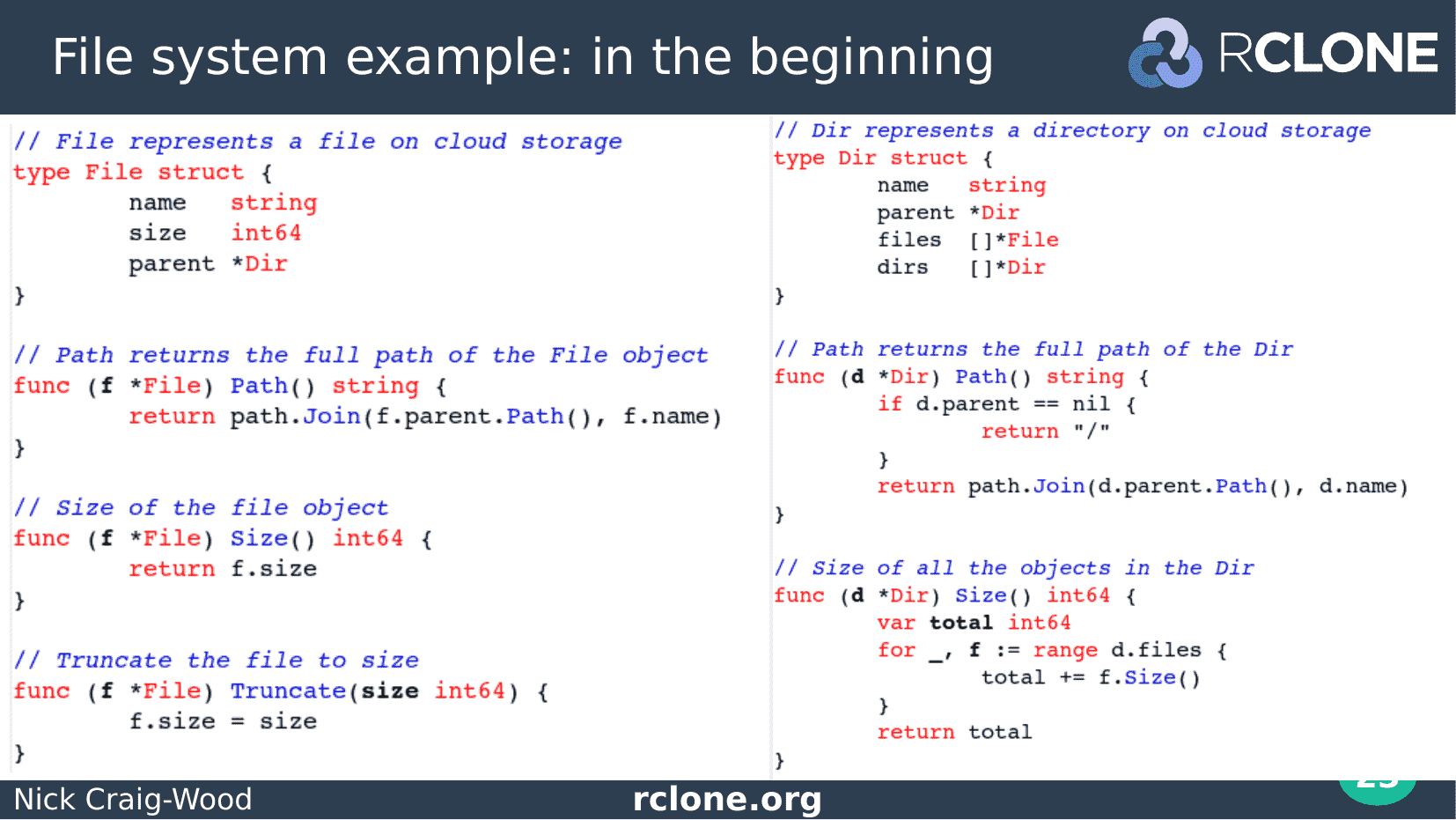

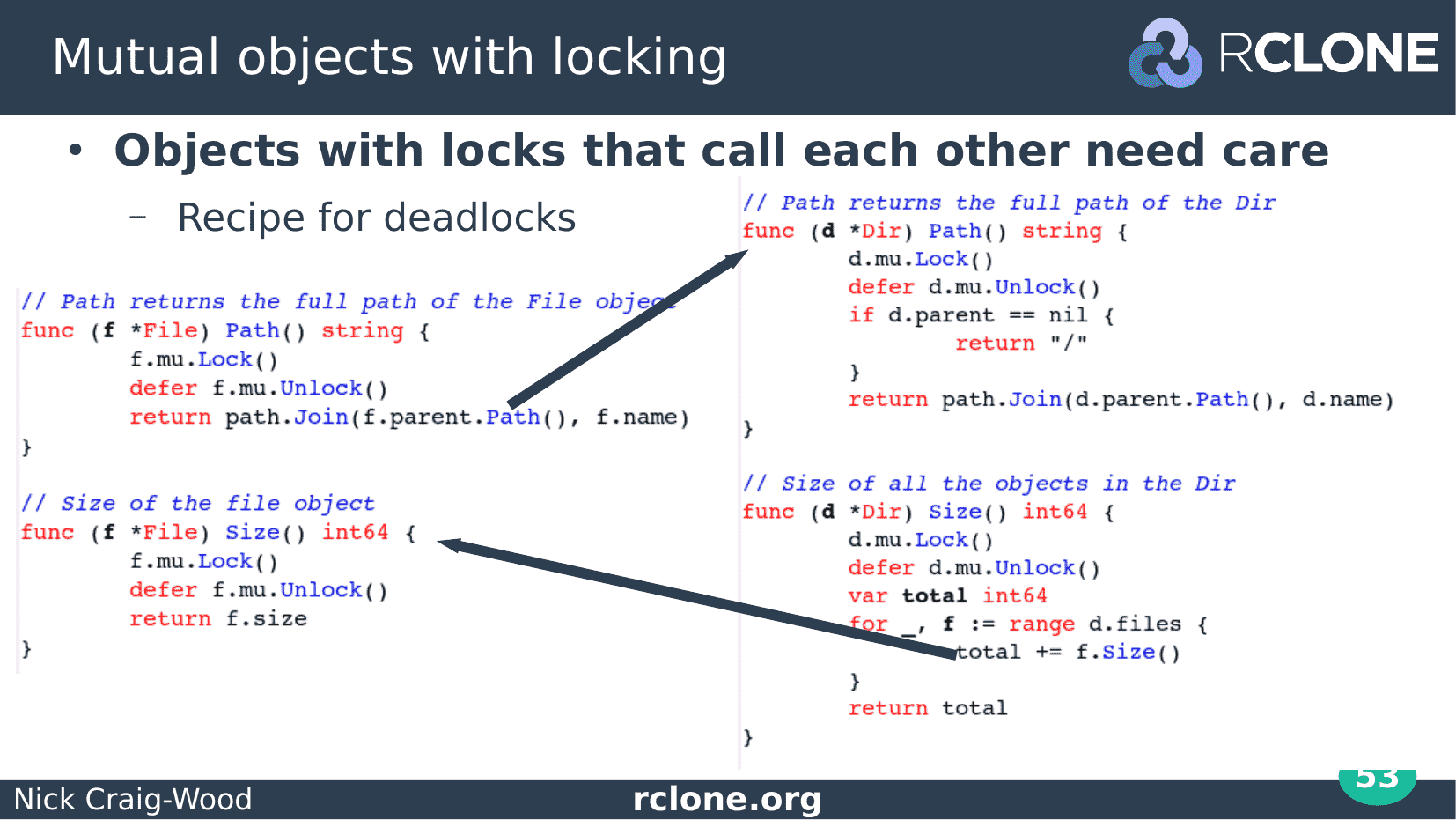

On the left you can see the definition of the File struct. It has a name, size and a parent directory. It has a Path method which returns the full path of the File and it needs to ask its parent directory for its Path in order to do that. It has a Size method to return its size and a Truncate method showing how the size of the file might get changed.

On the right we see the definition of the Directory struct. This has a name, a parent directory, a slice of files it contains and a slice of directories it contains. It has a Path method for returning its full path and it needs to find out the Path of its parent here. It also has a Size method which adds up the sizes of all the files in the directory.

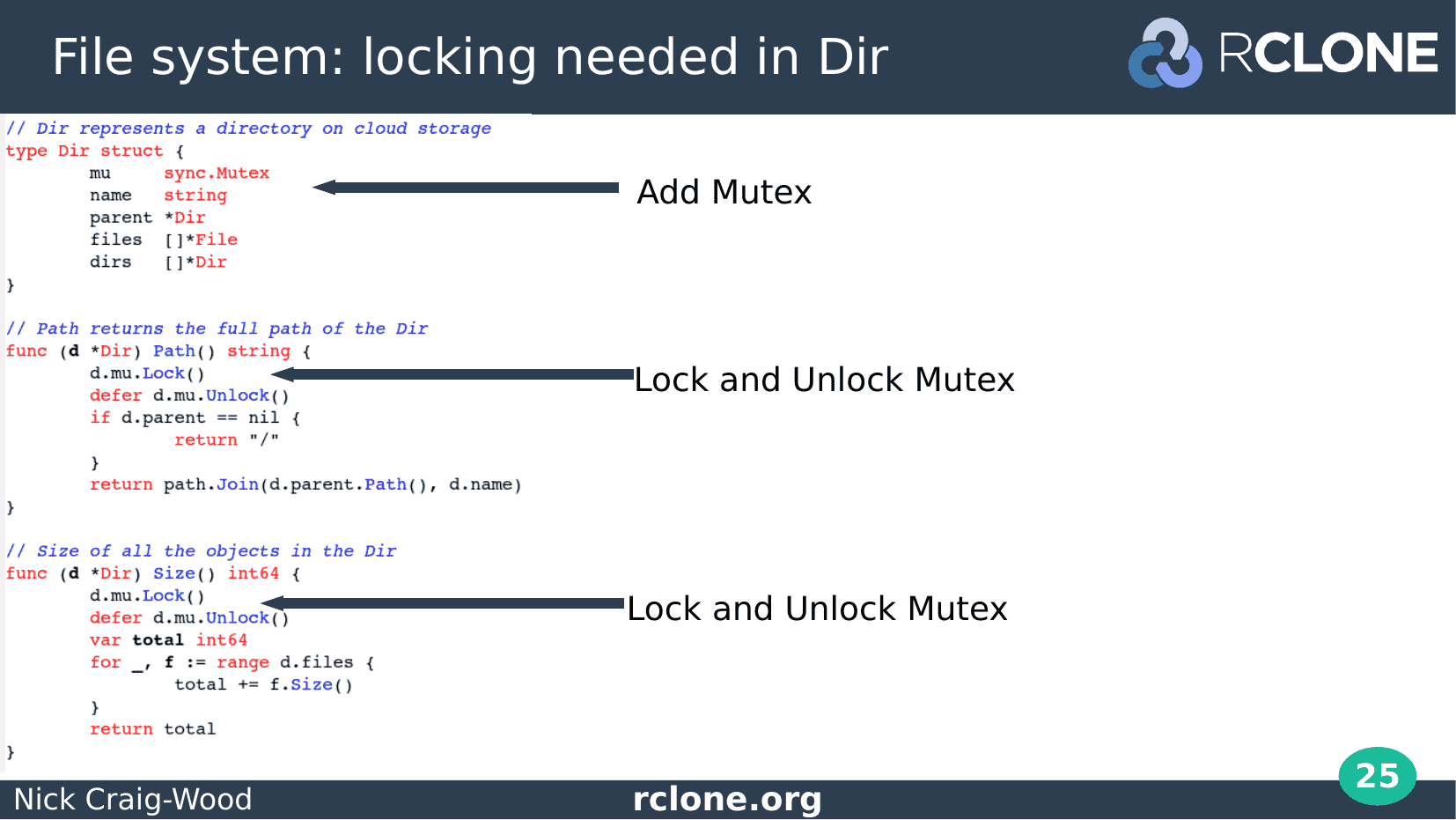

There is no locking in the code above, yet, but a few runs with the race detector reveals that locking is needed.

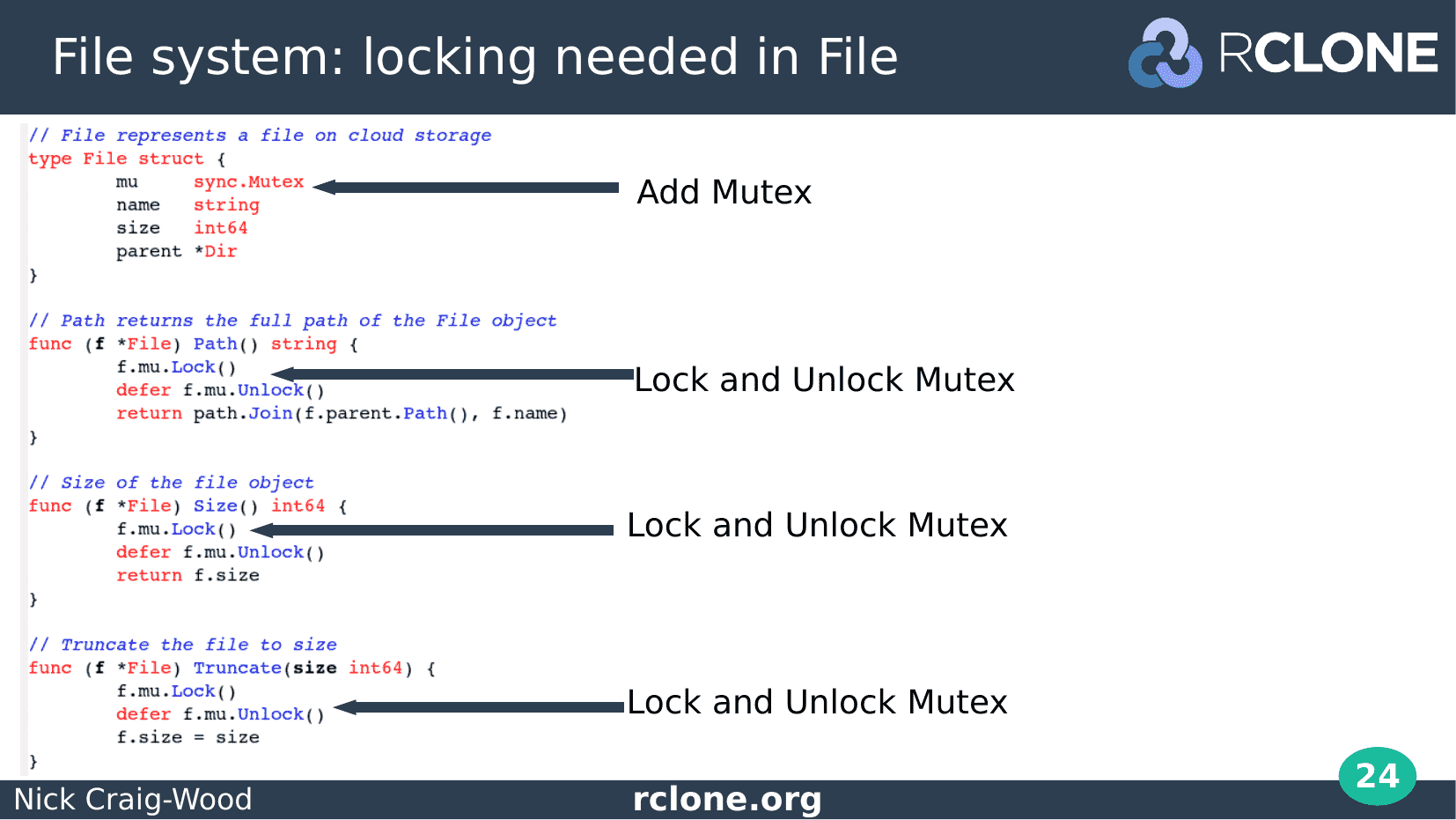

To prevent those nasty data races we add a sync.Mutex called mu into the File structure. The name, lower case mu is traditional in Go code.

Then in each of the methods we lock the mutex with mu.Lock() and defer the unlock of the mutex with the defer mu.Unlock().

This means that none of the methods will ever run concurrently and it means our instance variables are safe from data race corruption – hooray!

This is a standard pattern used in Go concurrent programming and hopefully you’ve seen it before.

Take the lock at the start of each method and defer its release to the end – what could possibly go wrong?

We do the same thing in the Directory structure, add a sync.Mutex called mu to the struct and then call mu.Lock() in each method and defer the mu.Unlock() until the method returns.

However we’ve unwittingly caused a potential deadlock by doing this.

I say potential deadlock here because when you run this code it will quite likely work just fine until just the right conditions are met.

Most deadlocks are like this – they don’t stop your code the first time you create them, they come back to bite you later when you are least expecting them.

Usually just after you’ve put your code into production.

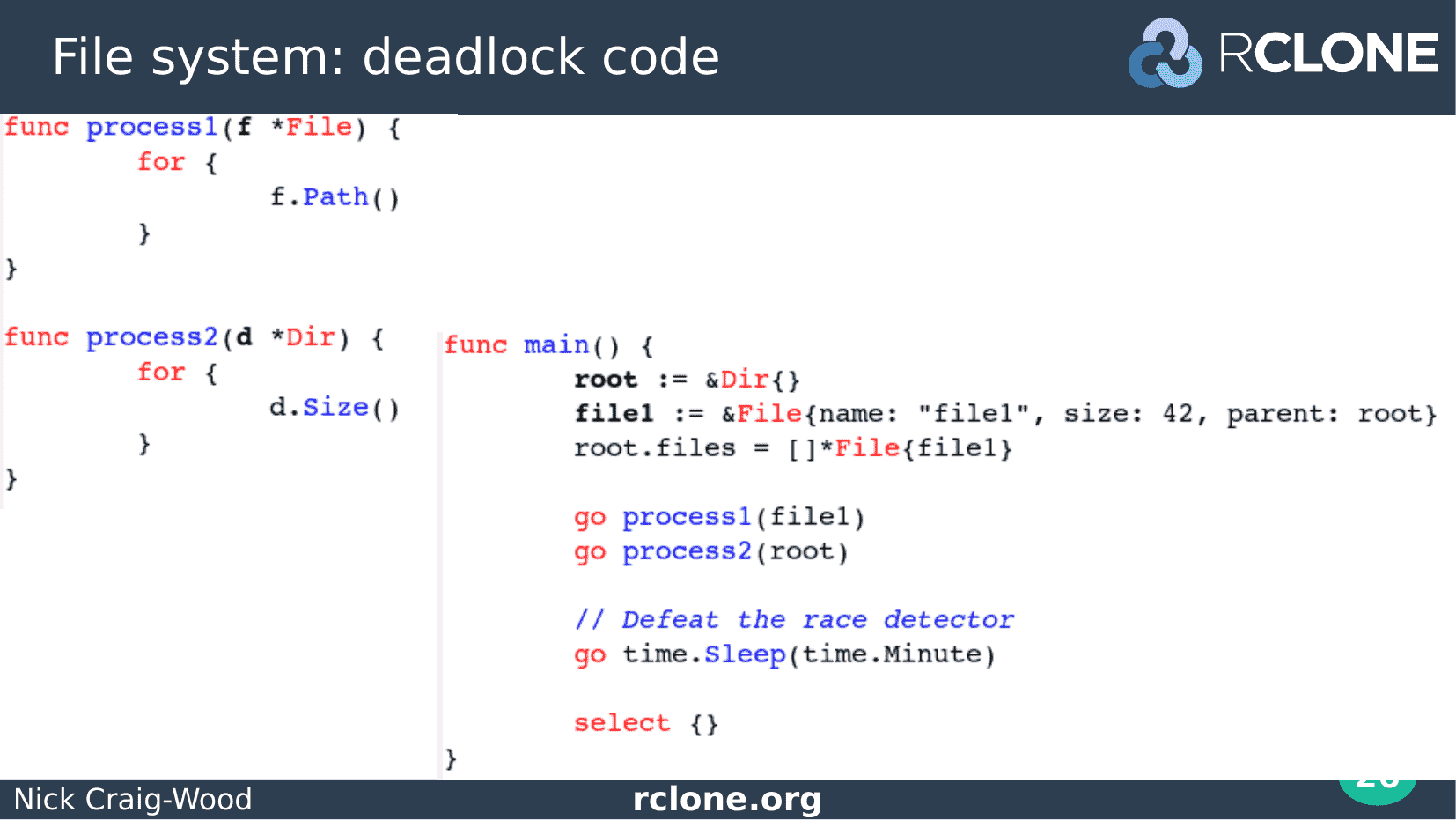

Here is a bit of code to exercise the Directory and File abstractions and which will provoke the deadlock.

Process1 just calls File.Path in a loop continuously. Not exactly normal usage, but we’re trying to provoke the deadlock here.

Process2 just calls Directory.Size in a loop continuously.

In our main function we create a root directory and put a file into it then start go routines to call process 1 and process 2.

We also start a race detector defeating go routine which just sleeps for a minute.

And finally the empty select statement to sleep the main go routine forever. Remember if we exit the main go routine then our program will stop, and we don’t want that.

So we run the program and it is now sitting there doing a whole heap of nothing while deadlocked.

How can we find out what it is doing?

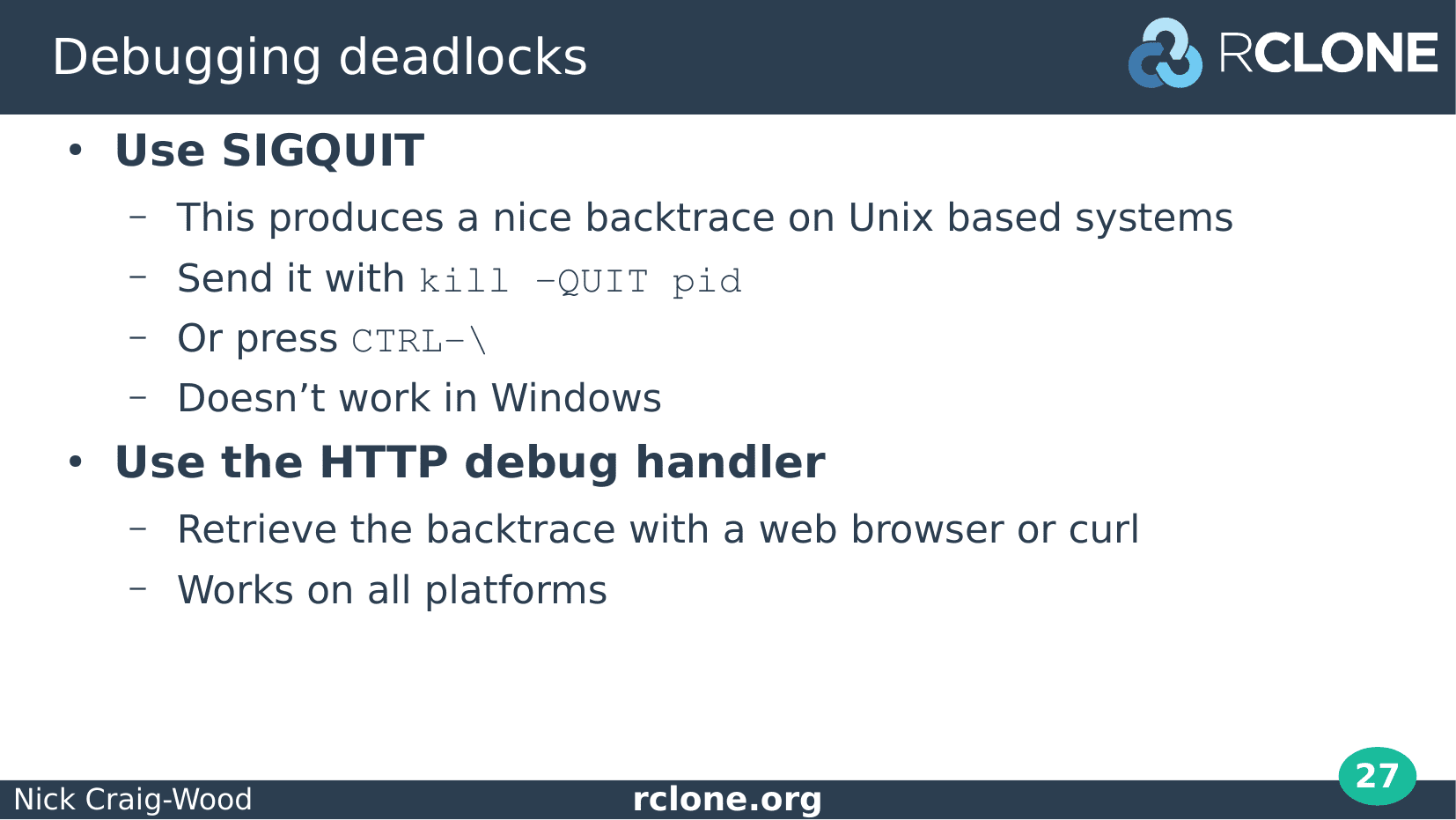

If you are running on a Unix based platform (for example Linux or macOS) then you can send the process a SIGQUIT using the kill command or press Control Backslash. This will produce a nice backtrace.

Windows platform users will have to work a little harder and install the HTTP debug handler from net/http/pprof and I’ll show how to do that a bit later.

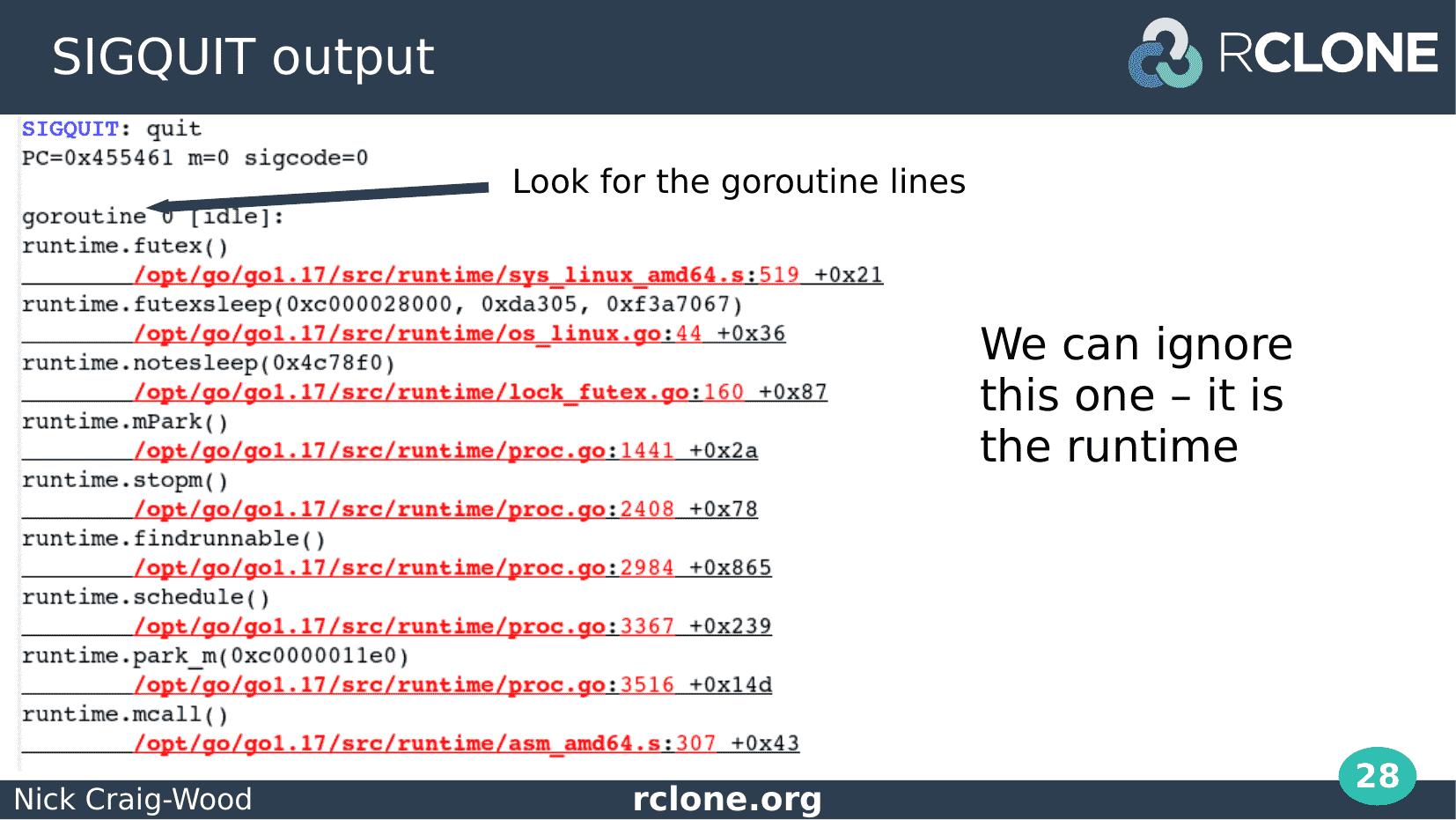

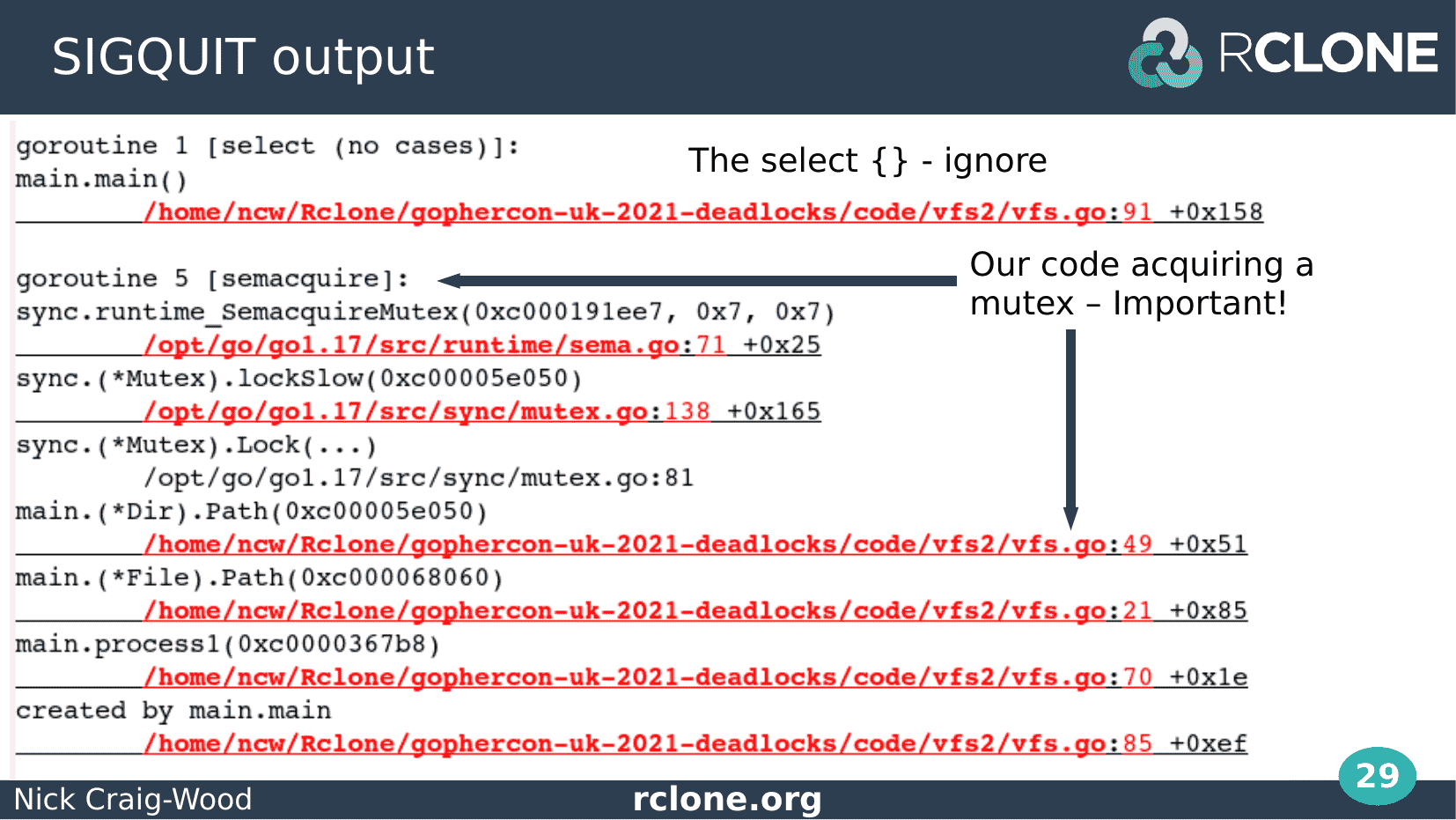

This is what happened when I sent the File and Directory example program the QUIT signal.

I got this nice backtrace. It’s quite long but there is a lot of stuff we can ignore.

The output is divided into stanzas and at the start of each one is a little description, Here it says goroutine 0, idle.

Following that is a reference to a line of source code, plus the code itself, once for each level of the call stack.

In fact this is a system go routine doing something in the runtime – we can ignore it because it doesn’t have any of our code in the backtrace.

Next we see go routine 1, select, no cases. This is the wait forever select code which we put in to stop the main function existing. We can ignore this too.

Next we see go routine 5 semacquire. This one is important, semacquire means it is blocked when trying to acquire a lock. For most deadlocks you are searching for these semacquire lines first.

Below the semacquire you can see a couple of lines of code in the runtime – these are in the sync.Mutex code, and finally a bit of our code in Dir.Path.

We can see that Dir.Path was called by File.Path so by the time the go routine tries to acquire the Directory lock it has already acquired the File lock.

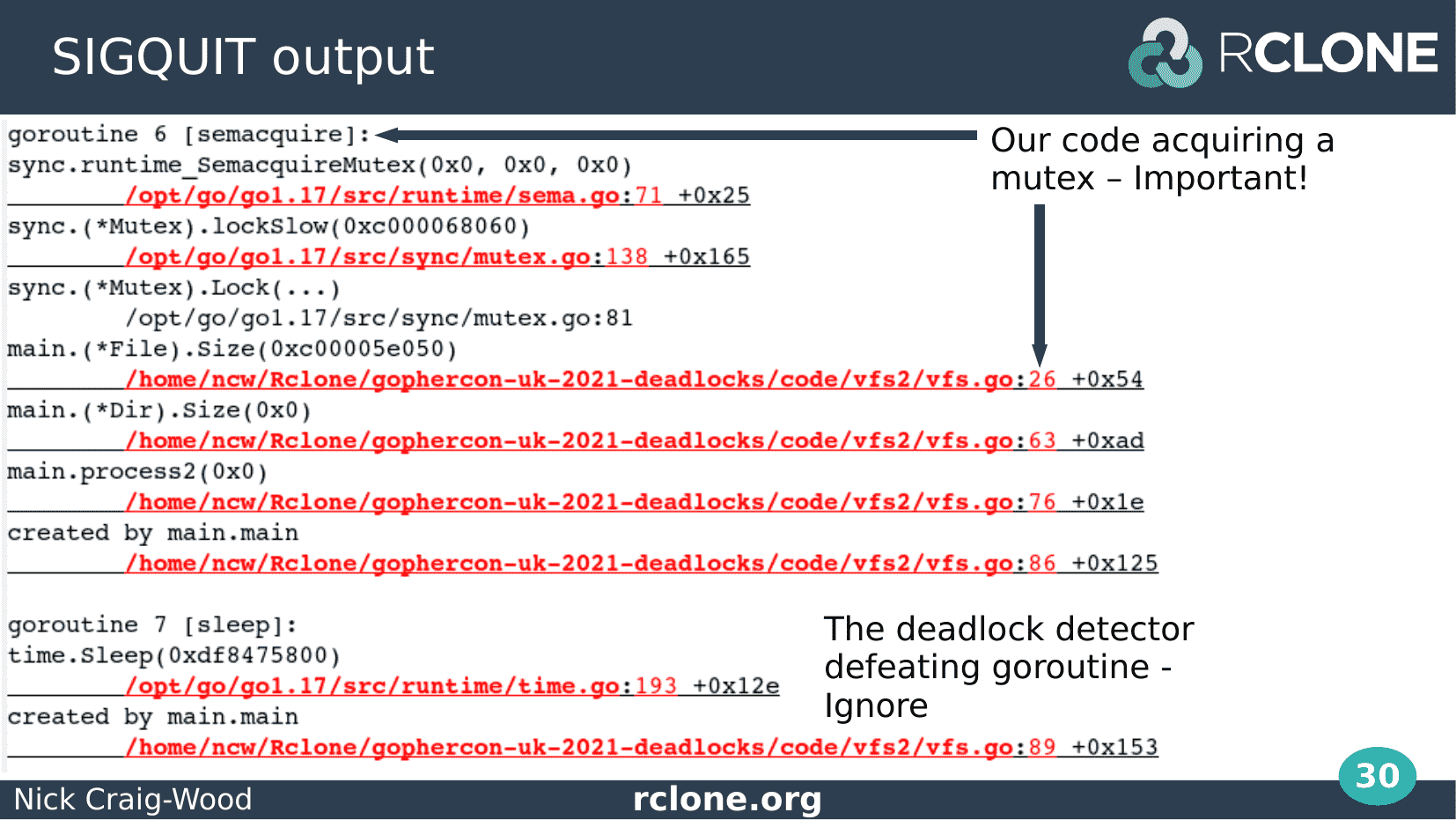

Next we see goroutine 6 – also blocked on semacquire.

It looks quite similar to the last one, two lines in sync.Mutex code and then it tring to acquire the mutex in File.Size.

Looking up the backtrace you can see that File.Size was called from Dir.Size which means that this go routine acquired the Dir lock first and is now blocked on trying to acquire the File lock.

If you have an editor you can click on those file names to jump to the code in question it is really helpful at this point so you can look up and down the call stack to see what other locks might be held.

Under that we see go routine 7 sleep which is our deadlock defeating go routine which we can ignore.

And finally the register dump which you can ignore for this purpose.

I’m sure the register dump is useful for low level debugging, maybe if you are writing assembler, but I’ve never needed it to debug deadlocks.

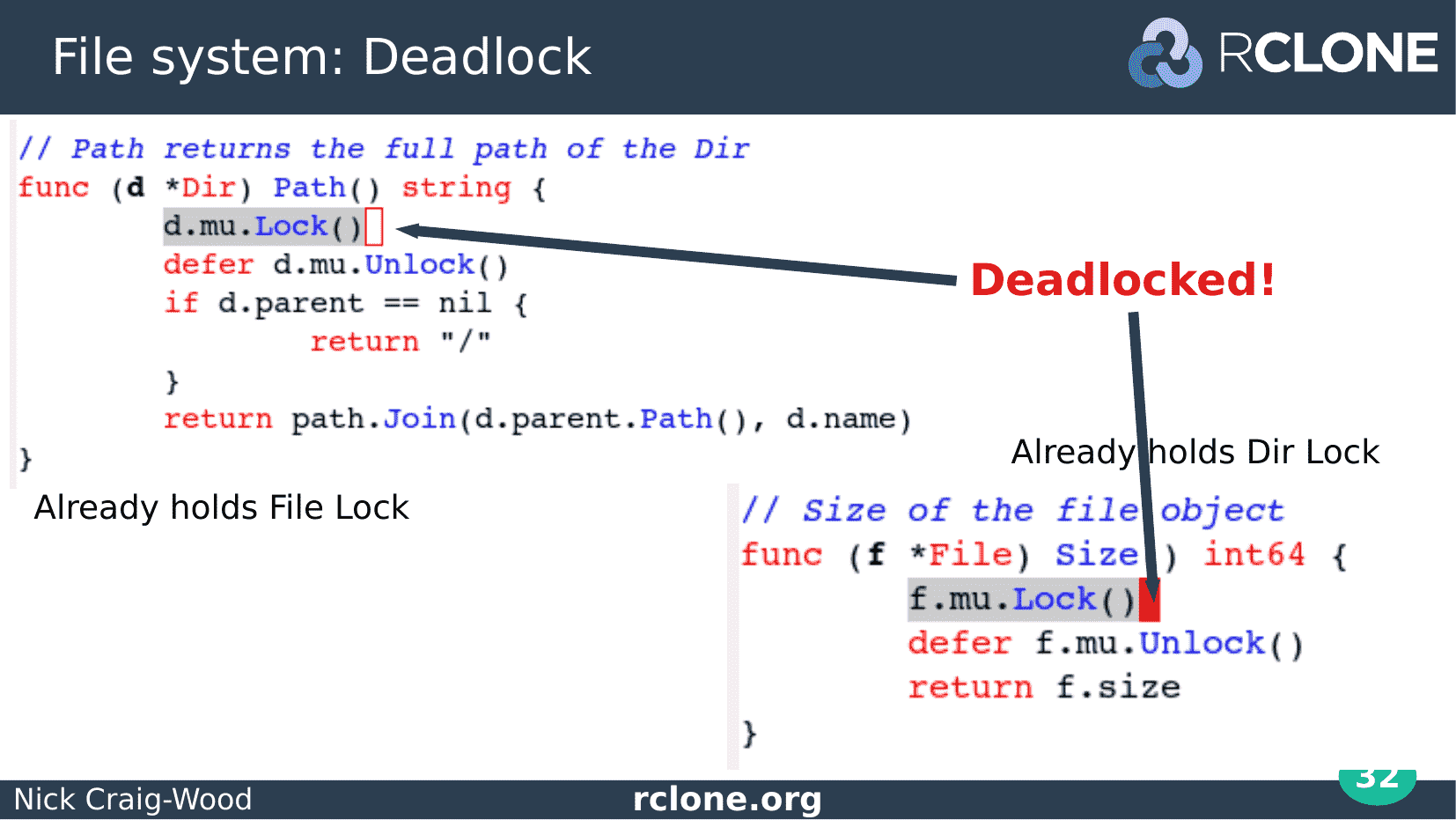

Here I’ve annotated the code from the backtrace showing where each go routine is blocked.

The fact that both parts of the code are blocked on acquiring a Mutex are very suggestive that there is a deadlock.

Let’s look at Dir.Path on the left hand side of the screen. We saw from examining the backtraces that this go routine already holds the file lock and is now blocked trying to acquire the directory lock.

On the right File.Size is already holding the directory lock but is blocked trying to acquire the file lock.

This means that these two functions are deadlocked and will block forever because the locks they are waiting for will never be released.

This deadlock occurs whenever the Size method on Dir is called concurrently with the Path method on File.

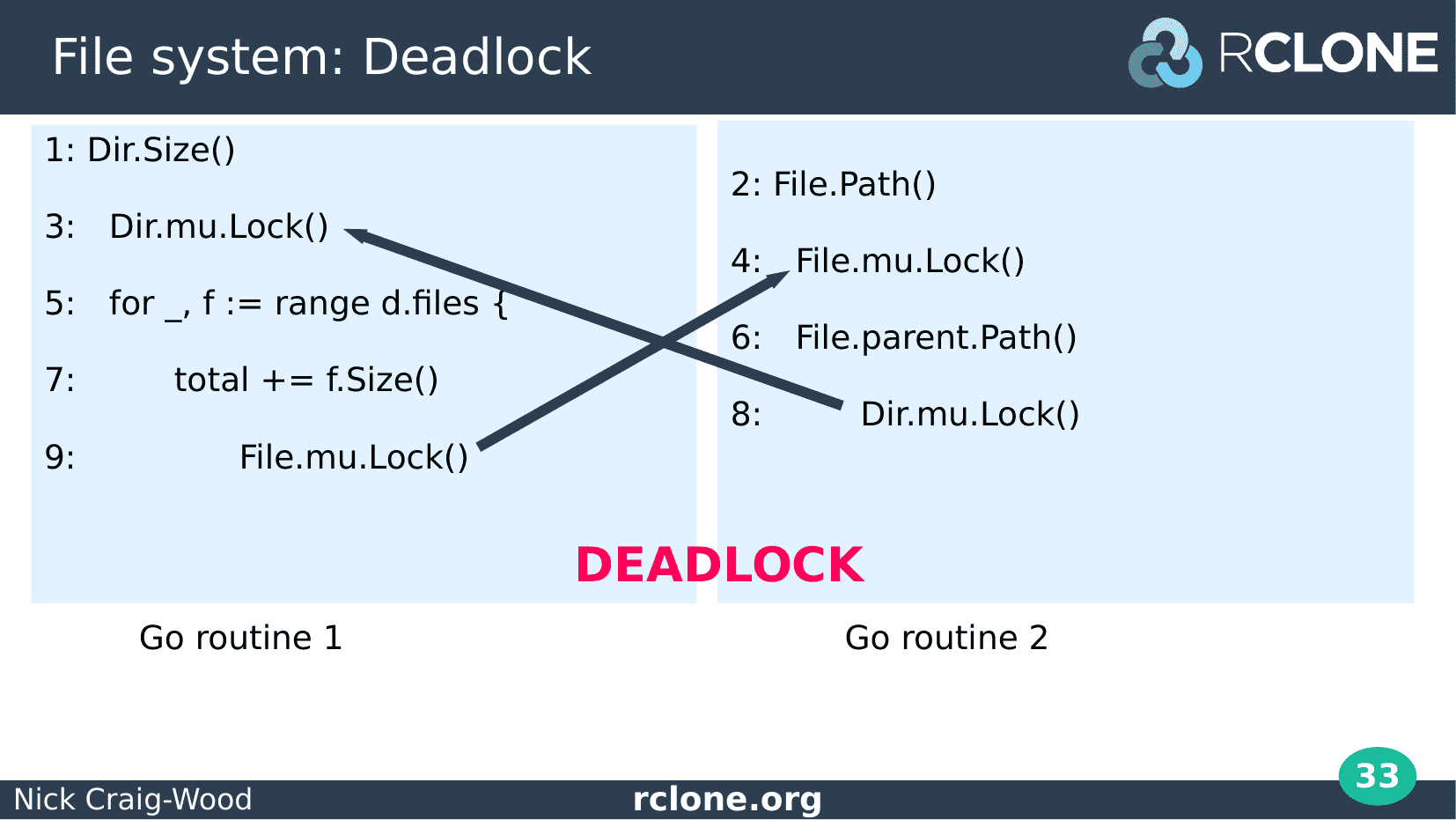

When thinking about deadlocks it is helpful to write out a timeline of the two processes involved. The numbers on the left of the code show the ordering of the calls to each process.

The arrows point from the blocked locks to the place the lock is held, and them crossing is very suggestive of a deadlock.

You might think that there is very little opportunity for this to happen given the short windows of opportunity – each of these instructions will be over in a few nano seconds won’t it? However, if the deadlock is possible it will happen sooner or later.

One thing to bear in mind is that locking instructions are particularly slow – they use slow memory locked instructions or schedule go routines or processes - which often turns something you thought would never happen into something which always happens.

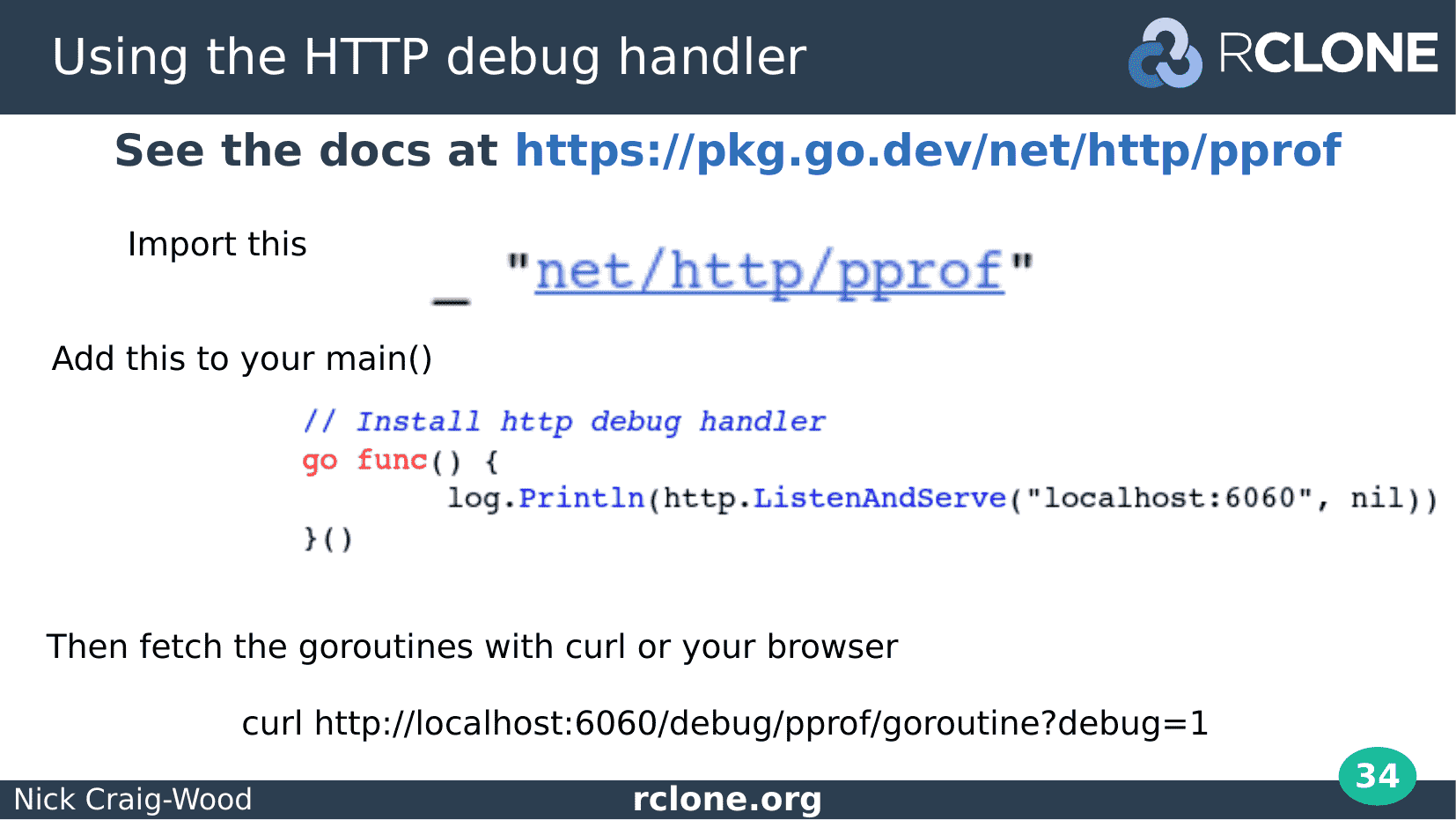

I’ll just quickly loop back to how to install the HTTP debug handler which you can use to collect backtraces when running Windows.

Look up the docs for net/http/pprof – everything you need is in there.

You can collect the output with curl or just look at in your browser.

You can use this on any platform of course, and you might consider leaving it in your production code for when your production code has deadlocked and you want to find out why.

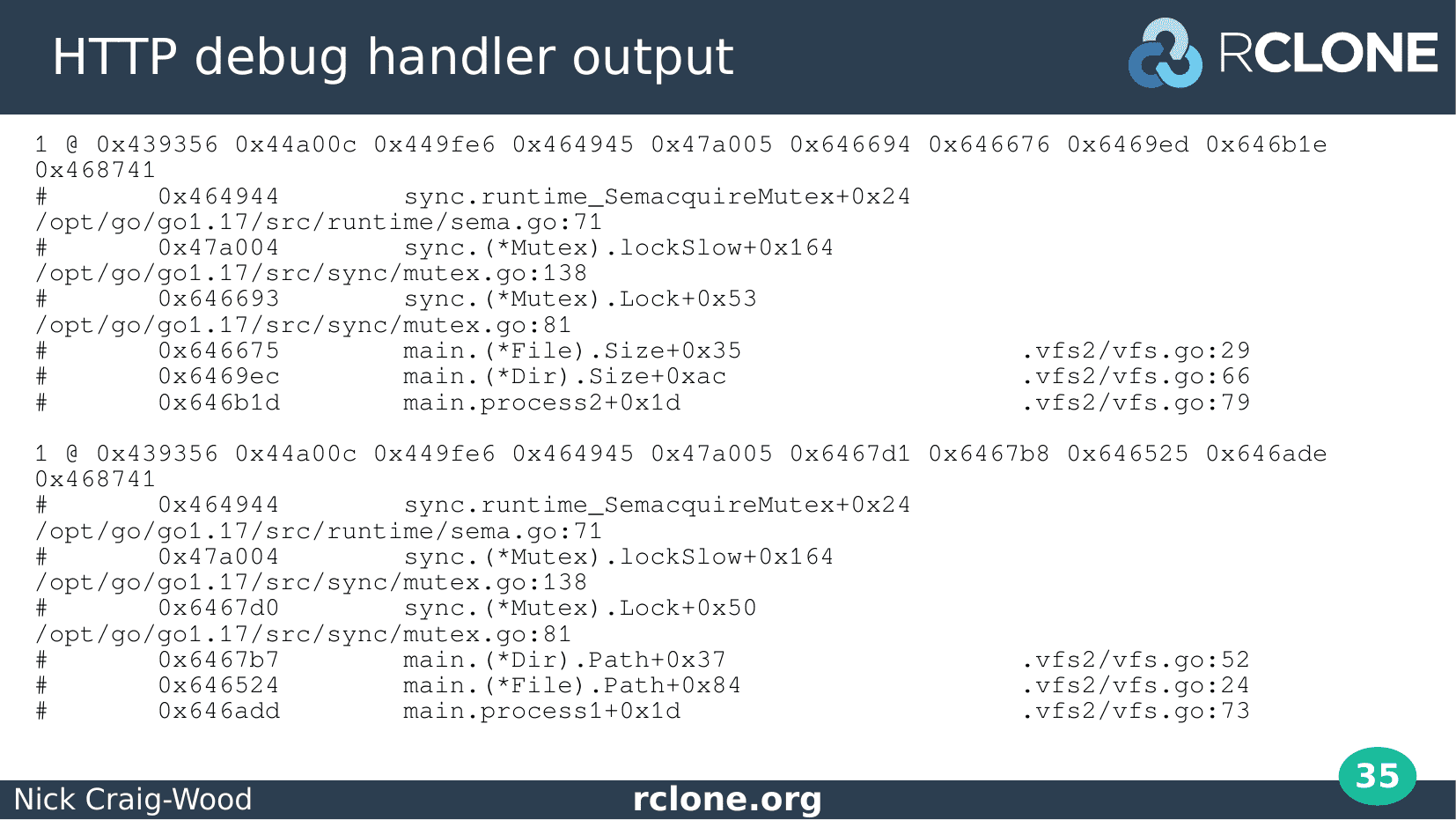

The output from the HTTP debug handler is similar to the output from SIGQUIT with one stanza for each go routine and a trace showing position in file and the actual line of code being executed.

It doesn’t call out the state of each go routine in the same way as the SIGQUIT output, but it is easy to see that the two go routines here are each blocked on SemaqcuireMutex which means blocked on acquiring a mutex as you might expect.

One important difference is that this output collapses goroutines with identical stacks which can very useful if you’ve got 1000s of goroutines.

When you are tracking down a deadlock in a real world program with lots of concurrency, you’ll find that the backtraces get very long, very quickly.

Deadlocks have a nasty tendency to spread through a good fraction of your running go routines until they are all waiting on a lock kind of like the way something crystallizes out of a solution.

Here is an example of an backtrace a user sent me while debugging an rclone deadlock.

It has nearly 2000 lines covering 260 go routines and is par for the course when dealing with lots of concurrency. There are 14 go routines blocked on acquiring a mutex, 123 blocked in a select statement, 121 blocked on sending or receving to a channel and 1 in a system call and 1 idle.

If that sounds like looking for a needle in a haystack, it is, we need some help here!

Luckily there is a great tool called panic parse which helps enormously here.

It condenses down that 2000 line log into a nicely coloured 142 line log with one stanza for each different type of go routine.

It shows that there are only 14 different types of go routine here which makes working out what is going on so much easier.

It also has a nice web output which I haven’t tried yet, but I’ve put up the screenshot from the github page so you can see what it is like.

This tool has saved me so much time when debugging deadlocks – thank you Marc-Antoine Ruel!

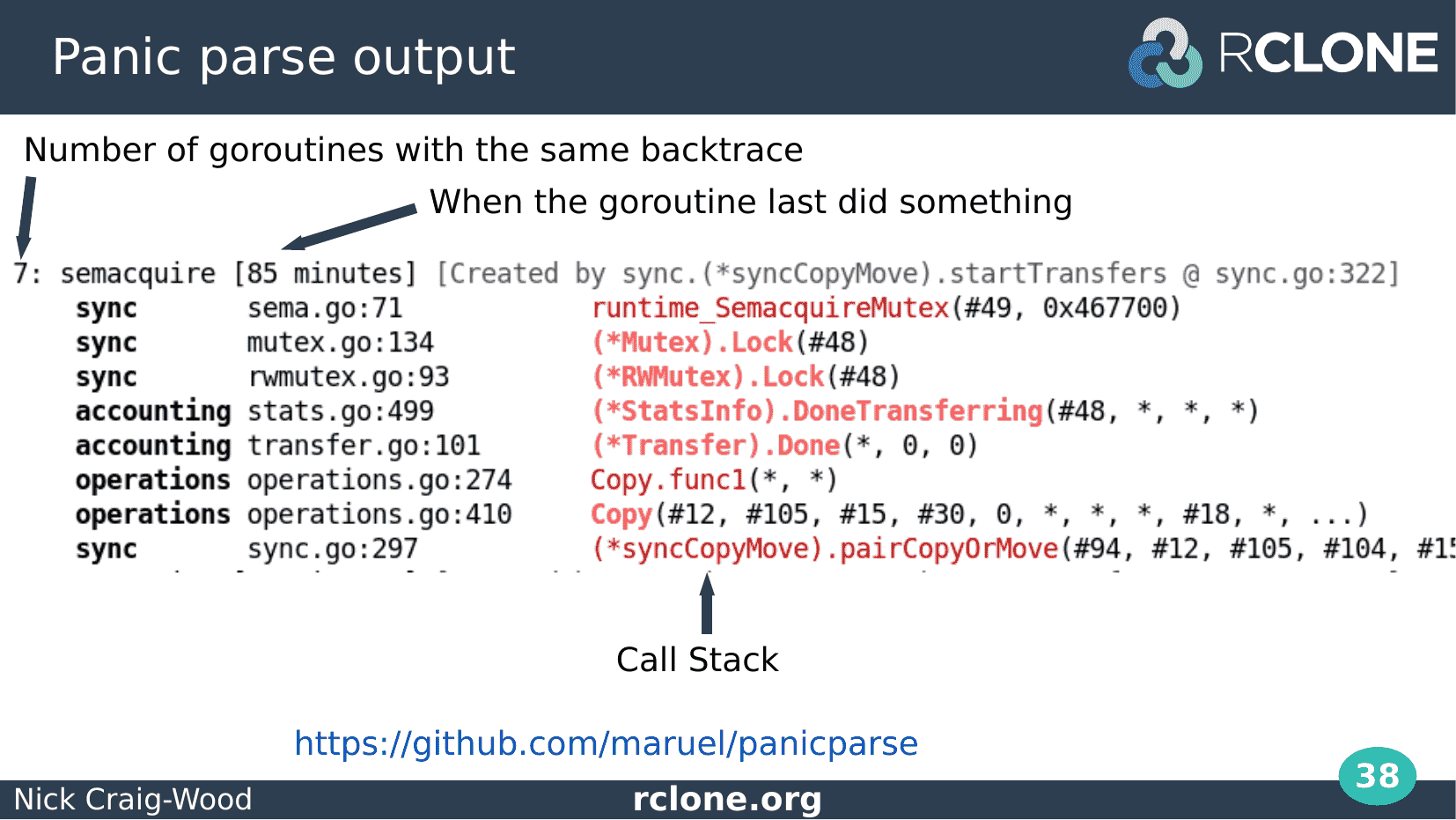

The text output of panic parse shows a stanza for each go routine. It collapses go routines with similar stacks together like the HTTP debug handler, but better.

Here is what a stanza looks like. On the left you can see a number – in this case 7 – this is how many go routines like this there were, and really usefully the time it has been paused. Looking for the first goroutine to pause can often be a big clue.

It is then reasonably easy to see that there are only a few go routines that could possible be the problem, namely the ones that are waiting on locks that have taken locks already so we can immediately ignore nearly all the go routines.

I’m not going to lie, it’s still tricky working out exactly what the cause of the deadlock from here is, but it is so much easier with panic parse.

How to avoid deadlocks

We’ve talked so far about what a deadlock is and how to find them and debug them, but a better strategy would be to avoid them completely.

I’m going to talk through a number of different techniques for avoiding deadlocks. Unfortunately there isn’t just one thing I can say – do this and you’ll never get a deadlock again, alas.

We’re going to start with some easy things to fix then move on to some harder problems.

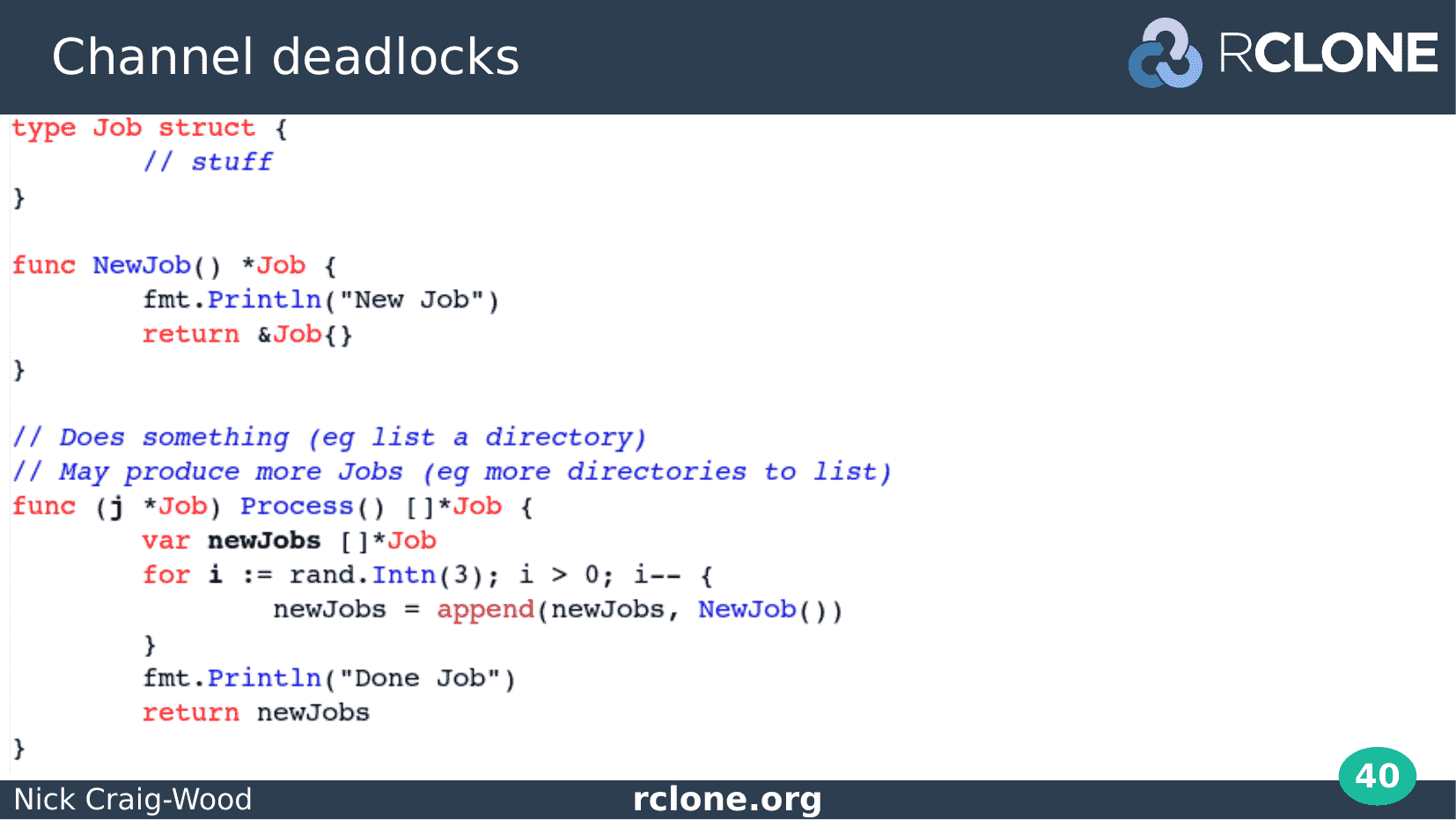

I said there was going to be an example of deadlocks with channels a bit later and here it is!

Let’s start with a Job. You can see its struct at the top.

It has a constructor NewJob which doesn’t do a lot in this example.

The Process method for each job runs the Job. However in the process of running a Job, more Jobs might be created. In this example it picks a random number as to whether to create more jobs or not.

Those jobs are then returned in a slice for further processing.

This is simplified from an rclone example where each Job listed a directory and returned jobs to list sub directories.

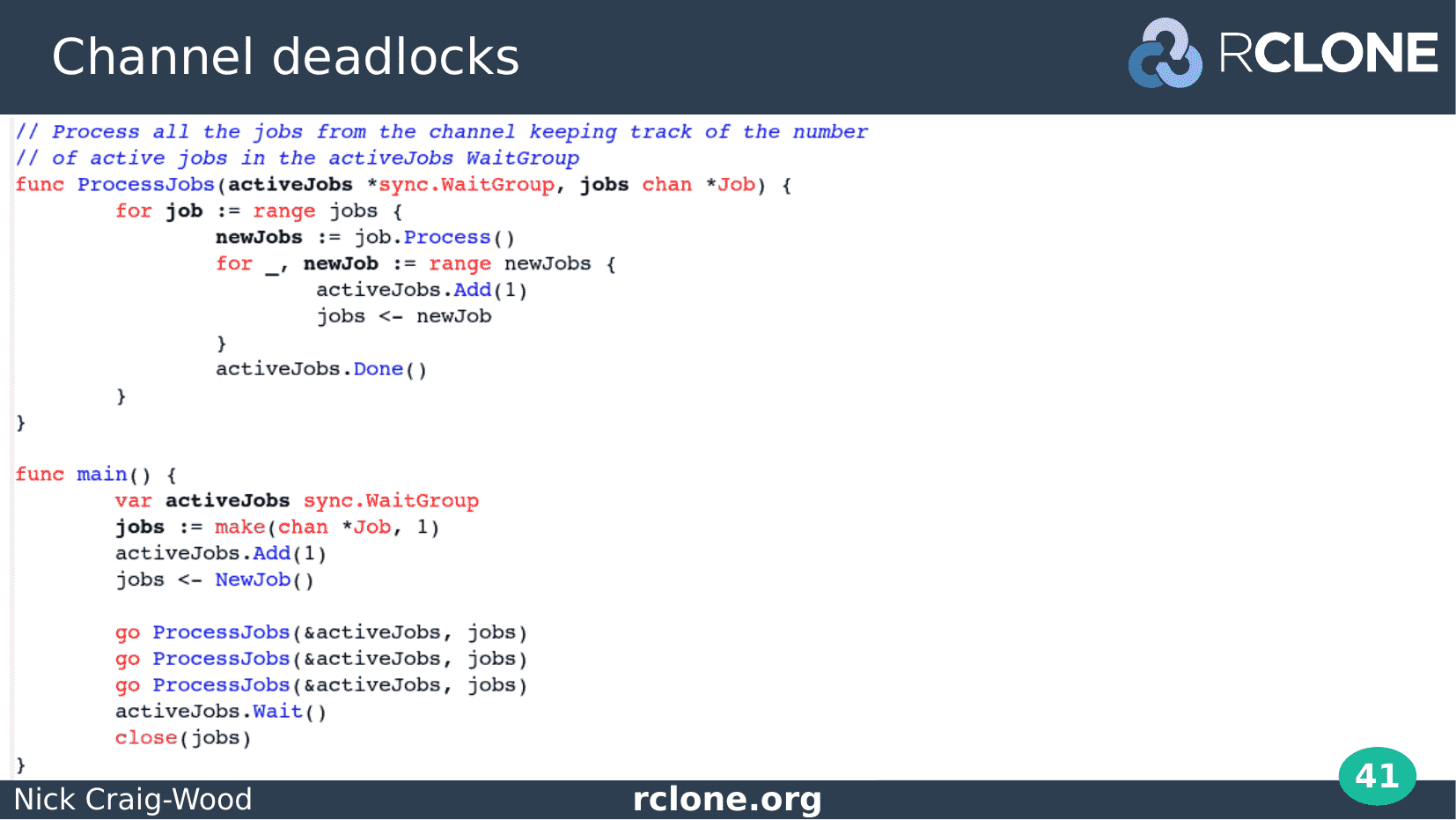

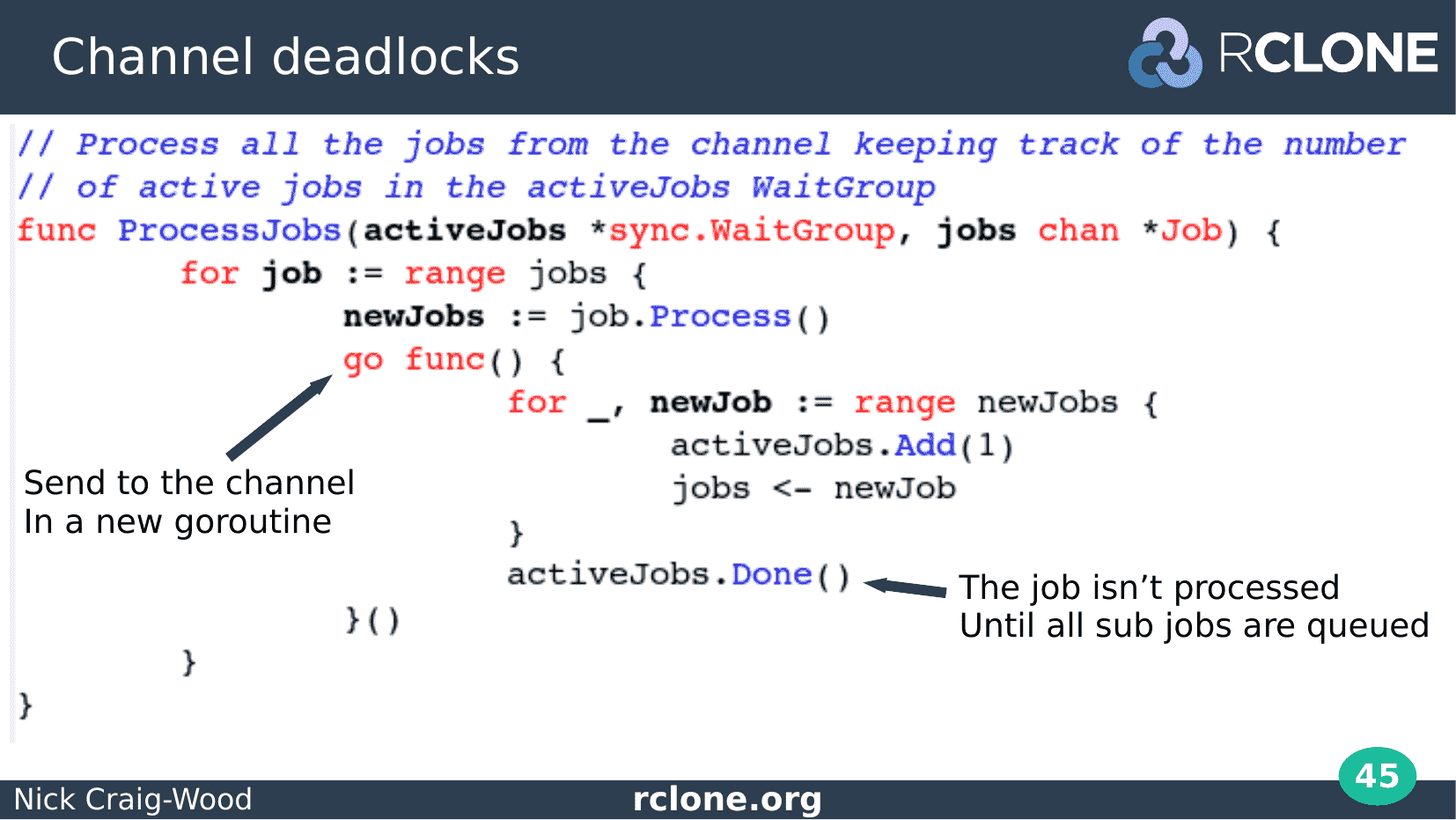

Here the ProcessJobs function takes a WaitGroup and a channel of jobs. When running it takes a job out of the channel, processes it and adds any created jobs back onto the channel.

It is written like this with a channel so we can run a few copies of ProcessJobs concurrently to increase the throughput and that is what happens in the main routine - We start 3 copies of the ProcessJobs function to increase the throughput.

Its worth explaining what the sync.WaitGroup does here. We are using it to keep track of the number of active jobs – whenever a job is created it is increased with the Add(1) method and whenever a job is finished it is decreased with the Done method.

When the wait group goes to zero, we know all the jobs have finished and we wait for that moment with the Wait method.

When we run it, it works fine for a while, running jobs, creating new ones, adding them to the channel, until...

… you guessed it, we get a deadlock.

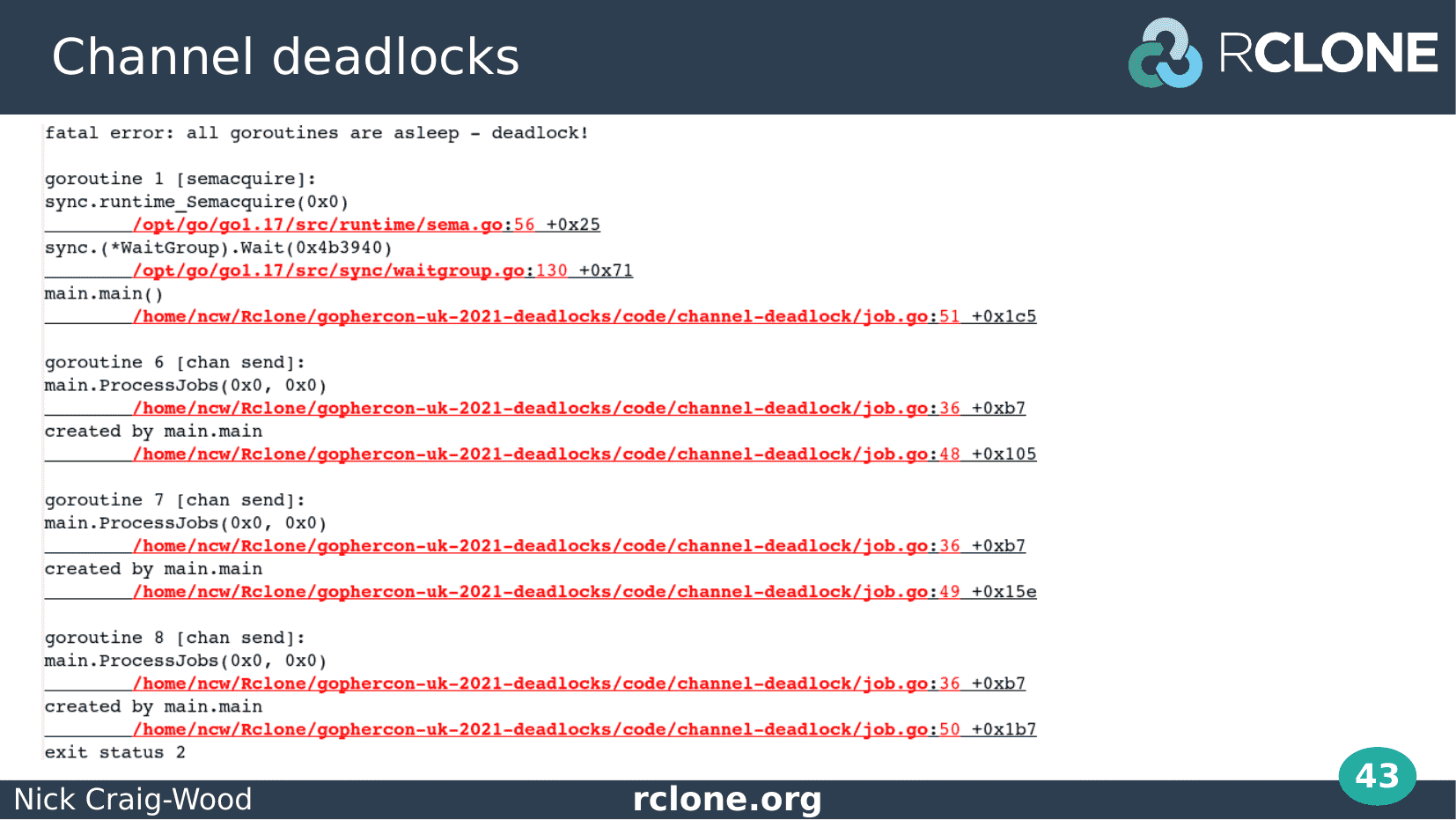

The first go routine shown, go routine 1, is our sync WaitGroup waiting for the others to finish.

Goroutine 6, 7 and 8 are all in state chan send. That is they are waiting for a channel to be emptied before they can send some data down it. You can see that they are all waiting in ProcessJobs.

The problem is that somehow all three of our go routines are blocked writing to the channel and none of them are reading from it.

Because those 3 go routines are the only place that we read from the channel, it means that the channel will never get emptied and those 3 go routines will never get unblocked, creating a deadlock.

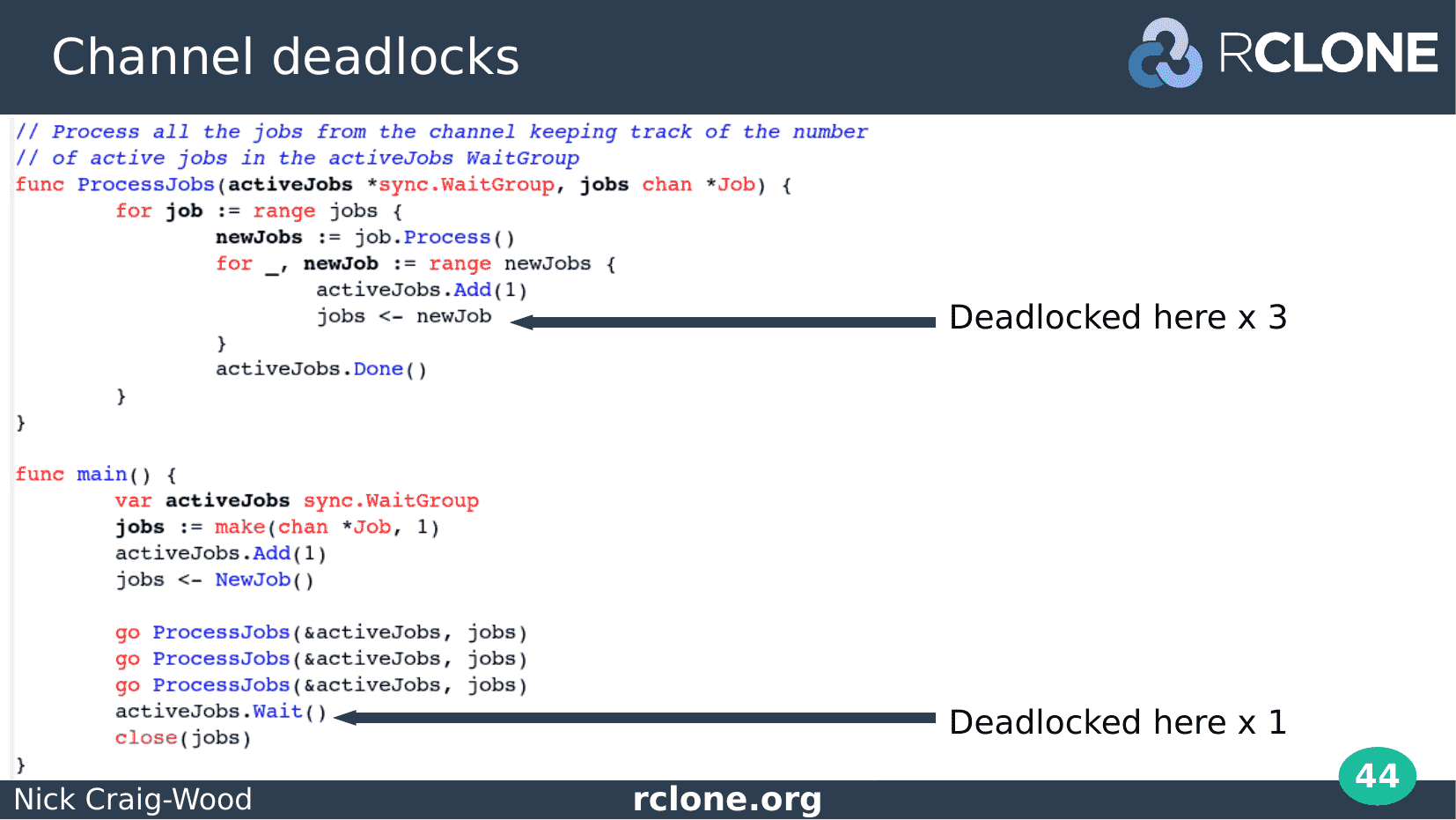

This is the code with the deadlock positions marked on it.

The three ProcessJobs functions are all trying to write a new Job into the jobs channel. However none of them is reading from the channel, so none of those writes will ever succeed A classic deadlock, this time with channels.

We can also see the sync.Waitgroup Wait method being called to wait for the Job processing to be complete. This is now part of the deadlock too as it will never proceed.

The Waitgroup Wait isn’t the cause of the deadlock, but it is collateral damage and this is very common when looking at deadlocks. Often the collateral damage overwhelms the cause of the deadlock and that makes it very hard to work out what is going on.

So what is the solution?

We need the ProcessJobs function to be either reading from the channel or processing a Job. We don’t ever want it to be blocked on writing to the channel, because if one go routine can get blocked then all of them can.

The easiest way of achieving this is by sending into the channel in a new go routine. The original Go routine is released to receive jobs from the channel while the new go routine sends the new jobs to the channel.

This has the consequence that there might be an indefinite number of go routines with a few jobs to add to the jobs channel hanging around. If that is a problem then a different design is needed.

Note we also moved the activeJobs.Done call into the new go routine – we can’t signal a job is finished until all its Job children are safely queued. If we do then the main function will end too early.

The moral of this channel deadlock is simple. Don’t send and receive to the same channel in the same go routine – it is a recipe for deadlocks.

As I said earlier this example came straight from rclone. This dead lock took some time to appear and it took me a few iterations to a find a solution which didn’t deadlock.

Concurrency is hard!

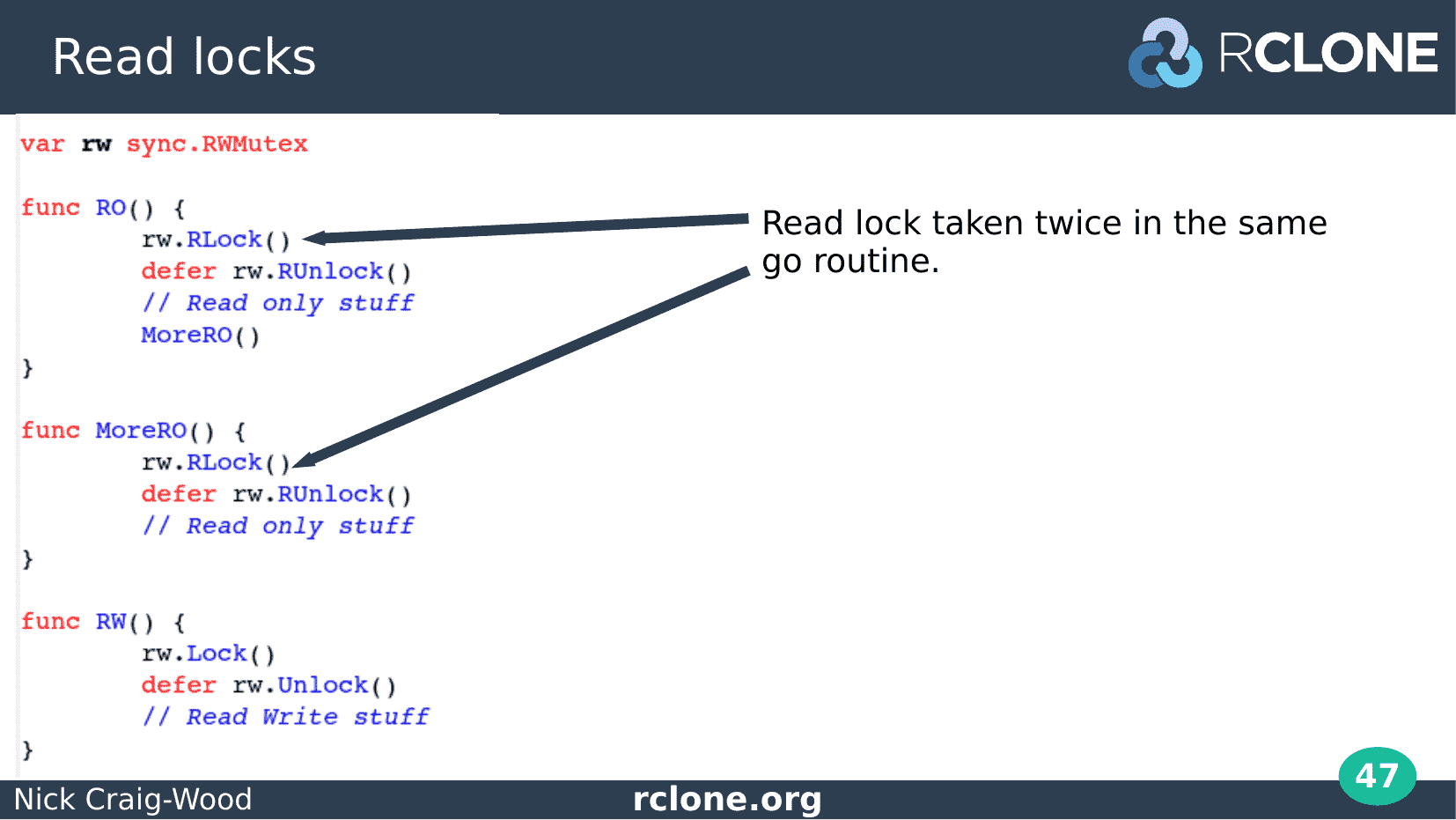

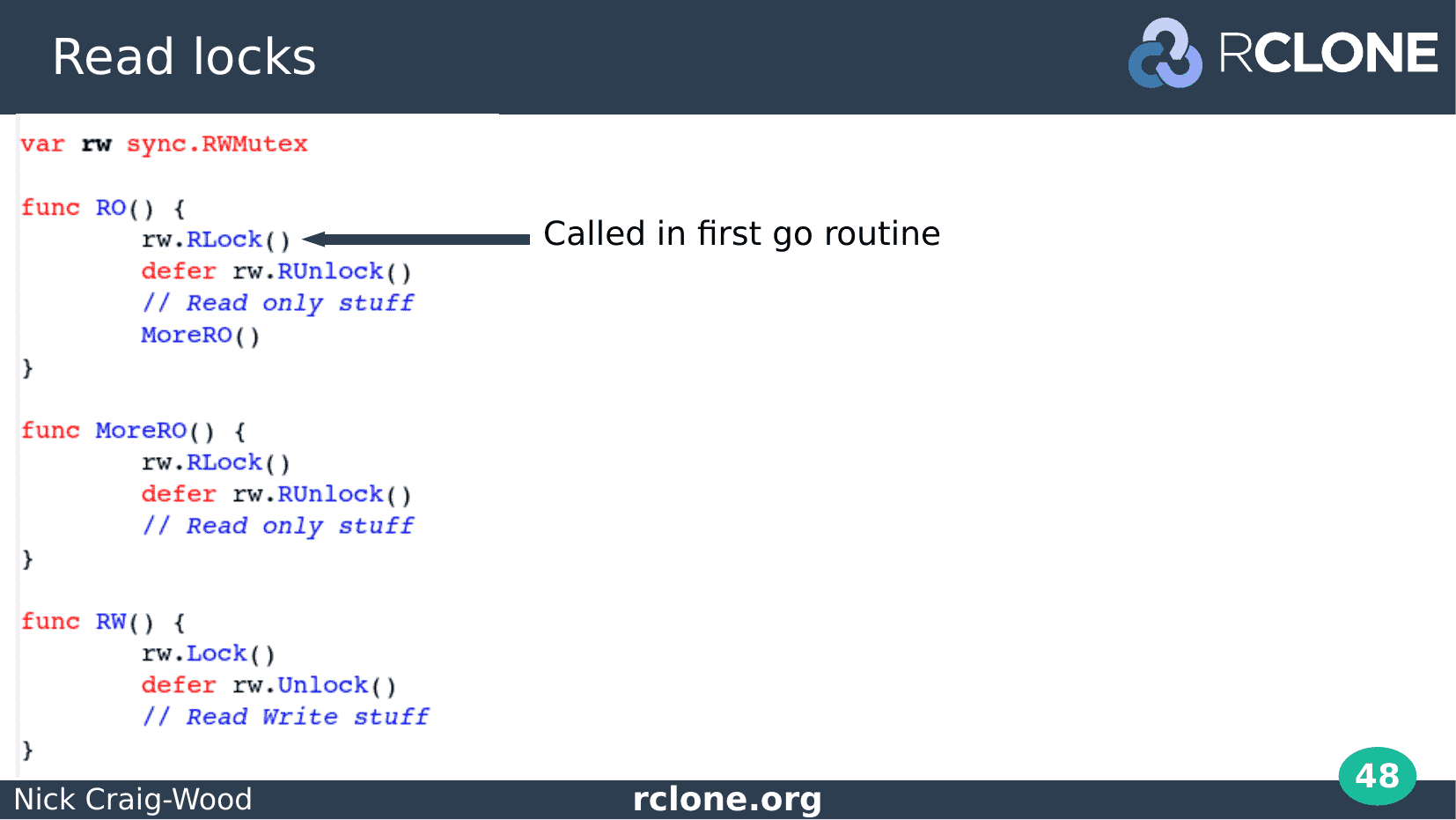

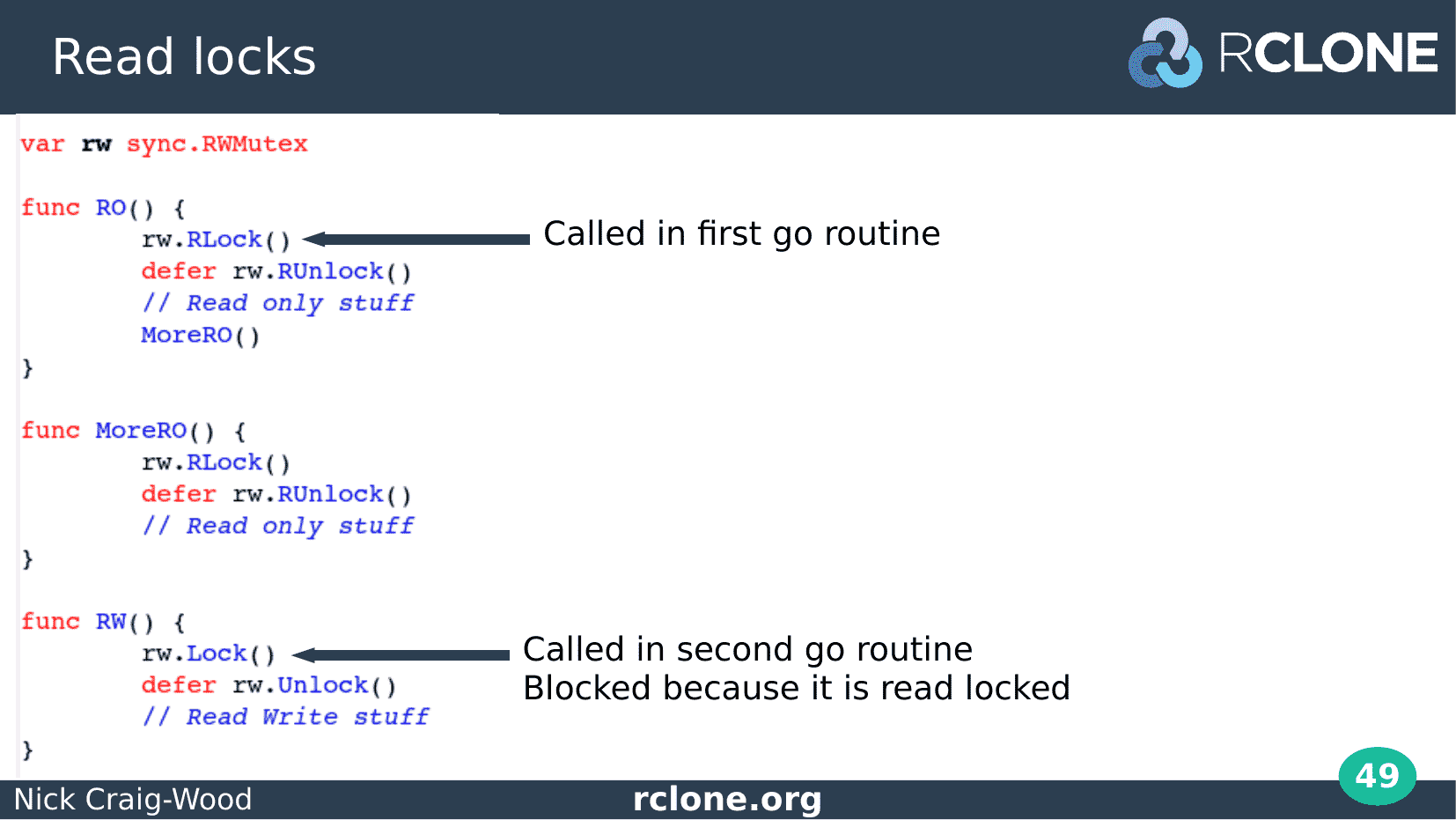

Here is an example with read write locks.

We have two main functions RO and RW. RO takes a read lock then calls MoreRO which in turn takes the Read lock again. This is allowed – read locks can be taken multiple times.

The RW function takes the lock for Write.

This look harmless and it works most of the time until suddenly it doesn’t and you made a deadlock as we’ll see in a moment.

This example is simplified from a real world example which was caused by a bit of careless refactoring.

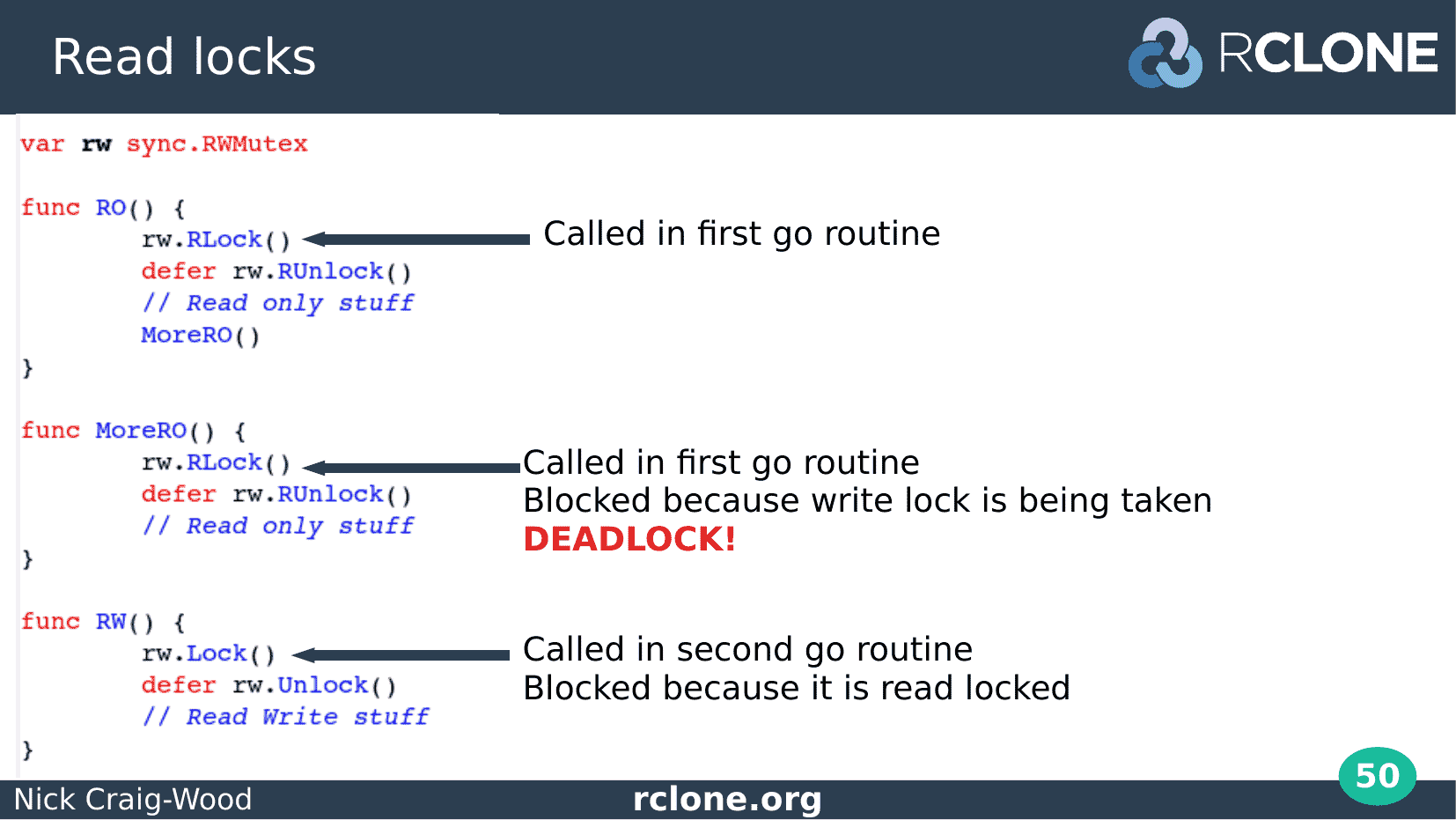

The next step is the Read Write lock being taken in go routine 2.

If you read the docs you’ll see a Read Write lock prevents any new Read locks happening so that the lock eventually becomes available.

There is also a note about recursive locking not being allowed if you read carefully which is exactly what this example is about.

The next step is the Read Write lock being taken in go routine 2.

If you read the docs you’ll see a Read Write lock prevents any new Read locks happening so that the lock eventually becomes available.

There is also a note about recursive locking not being allowed if you read carefully which is exactly what this example is about.

The deadlock happens when go routine 1 attempts to take the read lock again. This is called recursive locking and none of the standard library locking routines support recursive locking.

This lock is blocked because the Read Write lock in go routine 2 is in the process of being taken.

This means that MoreRO function will never return and the RO function will never release its lock, so in its turn the RW function will never acquire the mutex.

Thus, a deadlock!

And the moral of this story is Don’t take a read lock twice in the same go routine.

It might sound completely obvious but it is really easy to do by accident.

It does warn explicitly against doing this in the docs too, but of course I didn’t notice that until after I caused this deadlock!

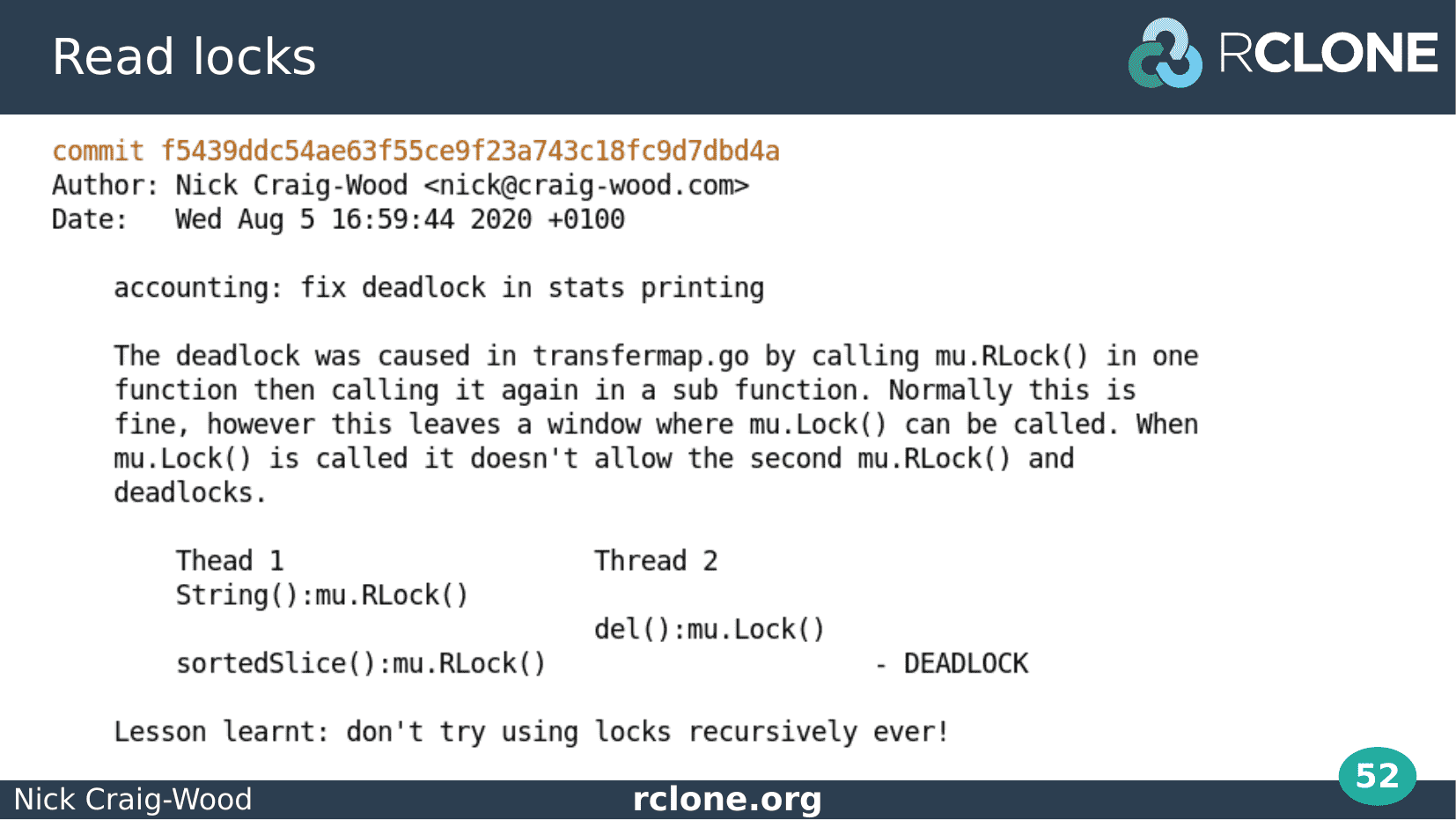

I could show a commit message for every one of the examples in this talk, but since we haven’t got all day I’ll just put this one up so you can feel my pain.

I always find debugging deadlocks hard even with all these nice tools, so when you have to debug one yourself, just remember that!

Objects which contains locks that call each others methods are a deadlock waiting to happen.

This happens naturally in more complicated systems, for example file systems, and great care needs to be taken not to cause deadlocks.

Going back to our Directory and File example, the problem is caused by the fact that Directory and File both call each other’s methods.

The general solution to this is called Total Lock Ordering but we’re going to look at some easier mitigations first.

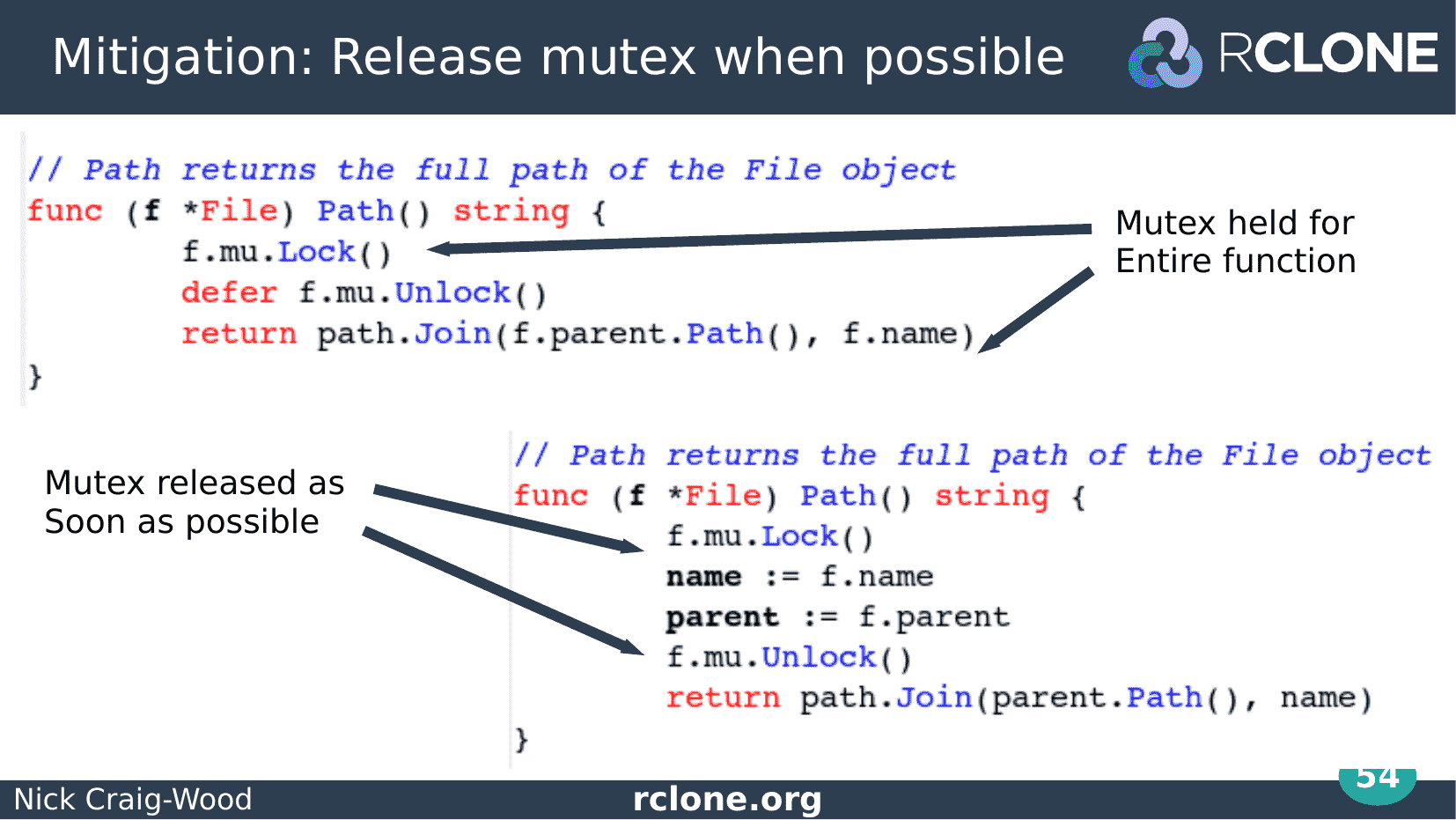

Here is one example fix for the deadlock. I call this technique shortening the locking Window.

What we’ve done here is released the mutex in the File Path method as soon as we can and in doing that the lock and unlock of the File and Directory mutexes no longer overlap.

At the top you can see the original function.

Below that you can see we’ve modified it to make a temporary copy of name and parent from the File then unlocked the mutex.

This is enough to fix the deadlock as shown before. It does introduce the idea that the Path function might return an out of date Path if the name or parent changes during the call of Path. Some thought is required here as to whether this is OK or not.

In order to minimize the chance of deadlocks, release locks as soon as possible to shorten the locking window.

Specifically release them before calling any other functions or methods which might take locks.

I’ve even resorted to using the defer statement to defer calls to get them outside the locking of the current method.

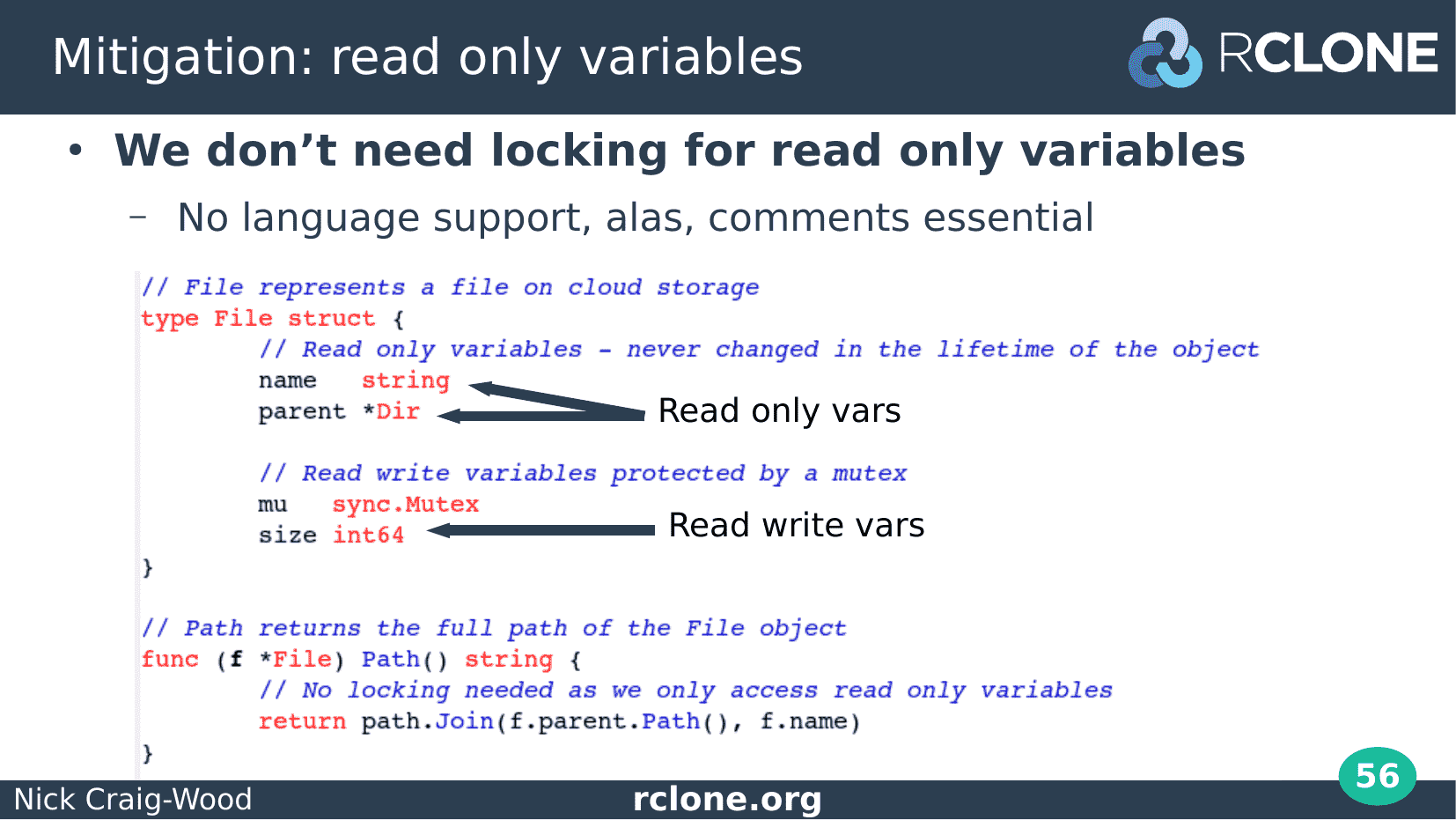

Another easy mitigation is to notice which members of your object are read only. These should be assigned to once in the initialization of the object and never written again.

These don’t need any kind of locking at all to access. Concurrent reads are always safe.

So, for example, here we say that the name of files and their parent directories never change.

I’ve moved them above the mutex definition to give the idea that they aren’t and don’t need to be protected by the mutex.

In this rename free world, we don’t need any locking in the Path method and we fixed the deadlock by not having any locking in the File.Path method at all.

If you can identify variables which are read only, you don’t need locking for them and they can be accessed outside the lock.

No locking means no possibility of deadlocks.

Here is a sketch of some other things you can do which I didn’t have room to make examples for.

Once way to reduce deadlock possibilities is to split the lock into multiple locks, so use more fine grained locking. This makes it less likely the locks will overlap.

Or maybe you can use atomics for some accesses (perhaps you are incrementing a counter). Atomics never block your process so can’t cause a deadlock. They come with their own caveats so use with care.

Using a Read write mutex is a great help for reducing lock contention provided you’ve got methods which only read things. Allowing many read only methods to run at once stops them blocking and minimizes the chance of deadlock.

And if you are using channels, buffered channels help avoid deadlocks because they don’t synchronize two go routines. Deadlocks can still occur when the channels get full though so it wont cure everything.

Now its time to bring out the big guns.

The ultimate solution to this kind of locking problem is to impose total lock ordering. This means that you are sure that if the locks overlap then you always take one lock first.

So if you have two locks A and B, you always take lock A before taking lock B in the same go routine. This makes sure we never have a deadlock.

This, however, is much easier said than done in a structured program with locks inside objects.

In practice with object based locks and methods, this means making one object super-ordinate and one subordinate.

For example this might mean that Directory can call File methods with the Directory lock held but File methods mustn’t call Directory methods with the File lock held.

In a perfect world we’d be able to specify what we want to a linter. I don’t think such a linter exists yet – if it does do tell! In the mean time comments like this one from rclone are what we have to live with.

It explains to the reader that the Cache and Item objects are tightly linked and that if you don’t want to cause a deadlock then don’t call Cache methods from Item with the Item lock held.

This means that when you change code you need to be very careful to uphold those invariants. If you don’t, deadlocks will ensue.

So make write of comments and do lots of code review when writing this sort of code.

Debugging deadlocks can get very hard, very quickly and I used to think I was pretty good at this computer science stuff, but debugging deadlocks frequently makes me feel very stupid.

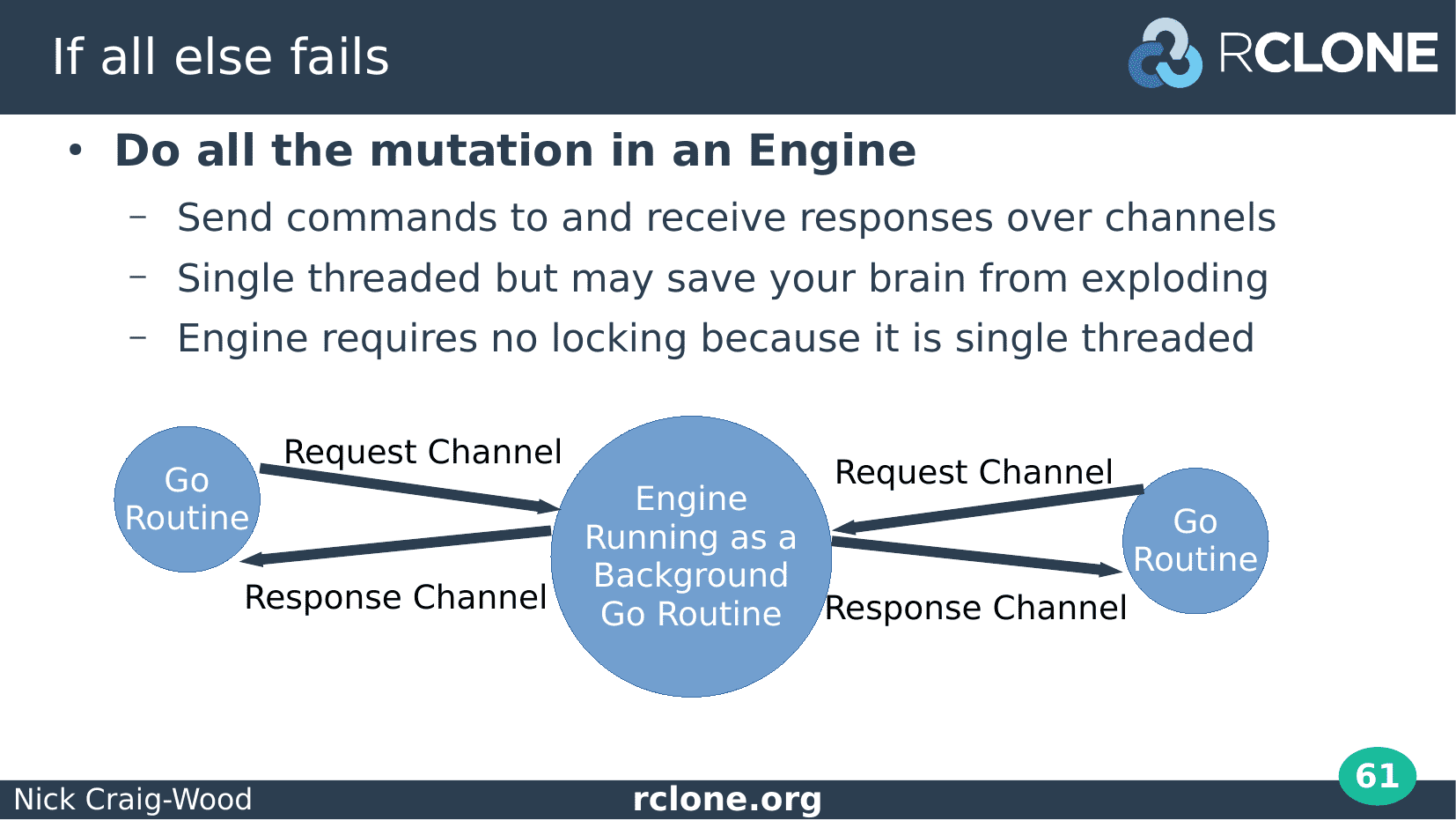

So if the locking gets too complicated then you can bail out and use a single threaded engine to remove all the locking.

Single threaded likely means lower performance but maybe having no deadlocks is worth it.

You’d communicate with the engine over channels in a request / response style. Typically you’d send the channel for the response over the request channel.

This makes things much simpler and is very much in the classic Go style but making everything single threaded will drop your performance which may be unacceptable.

You’ll notice there’s been a lot of struggle with deadlocks in the previous slides and it would be nice if there were tools to help us find the deadlocks before they happen.

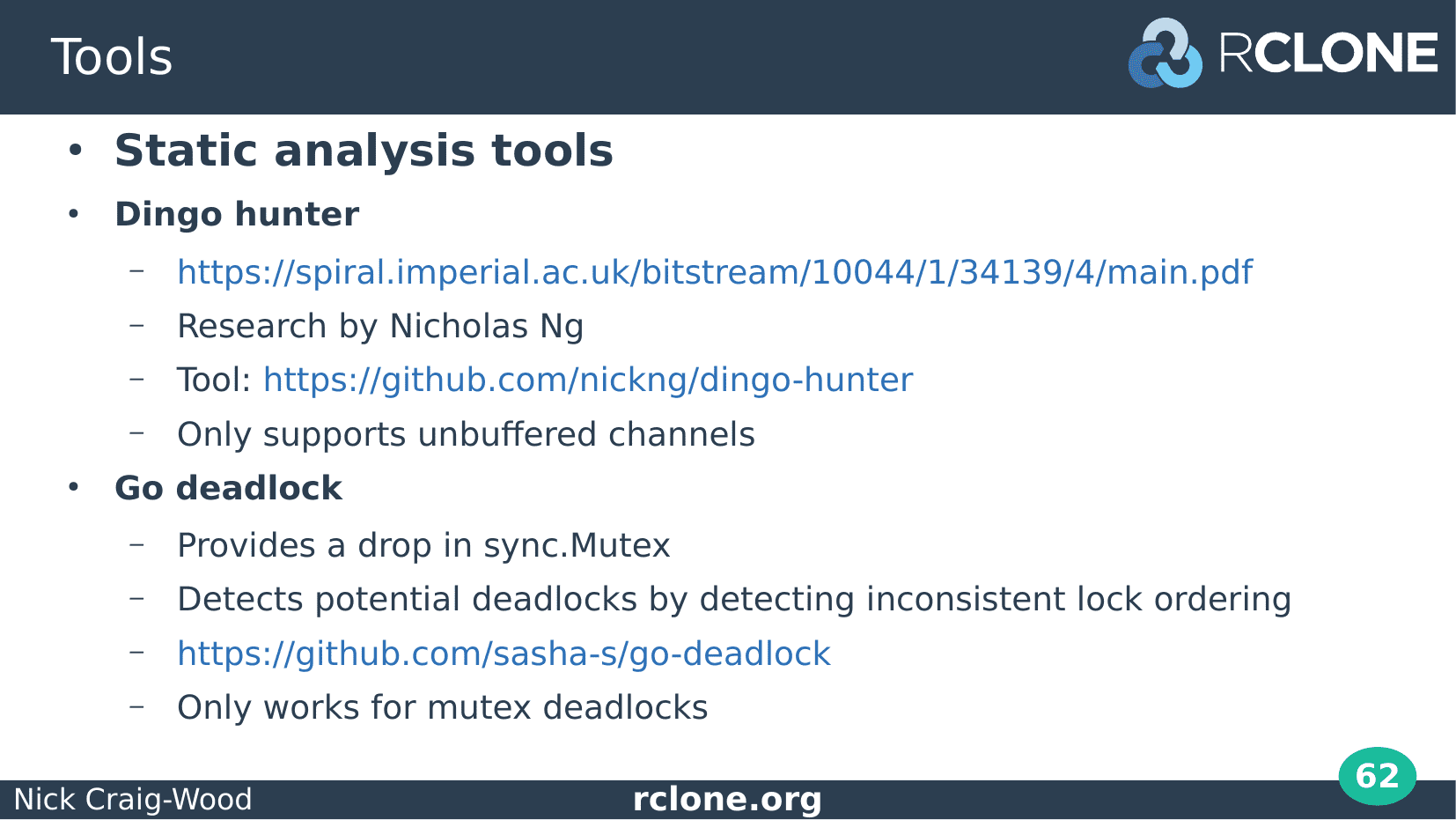

Well there are a couple of notable tools for finding deadlocks in go code.

Dingo hunter is based of a theoretical approach for finding channel based deadlocks. You may have caught the talk about it here in 2016. It only works for unbuffered channels, alas, which limits its scope.

Go deadlock is a practical tool for finding violations of total lock ordering and has been used to find deadlocks in Cockroach DB for example. I’ve used it on the rclone code base a few times.

It comes up with error messages that look rather like those from the race detector, but unlike the race detector it detects potential deadlocks before they happen so you can run this on your code which hasn’t deadlocked yet.

Go deadlock only works for mutex deadlocks, not channel deadlocks. As I said before this is probably 90% of the deadlocks I see so it is an excellent start.

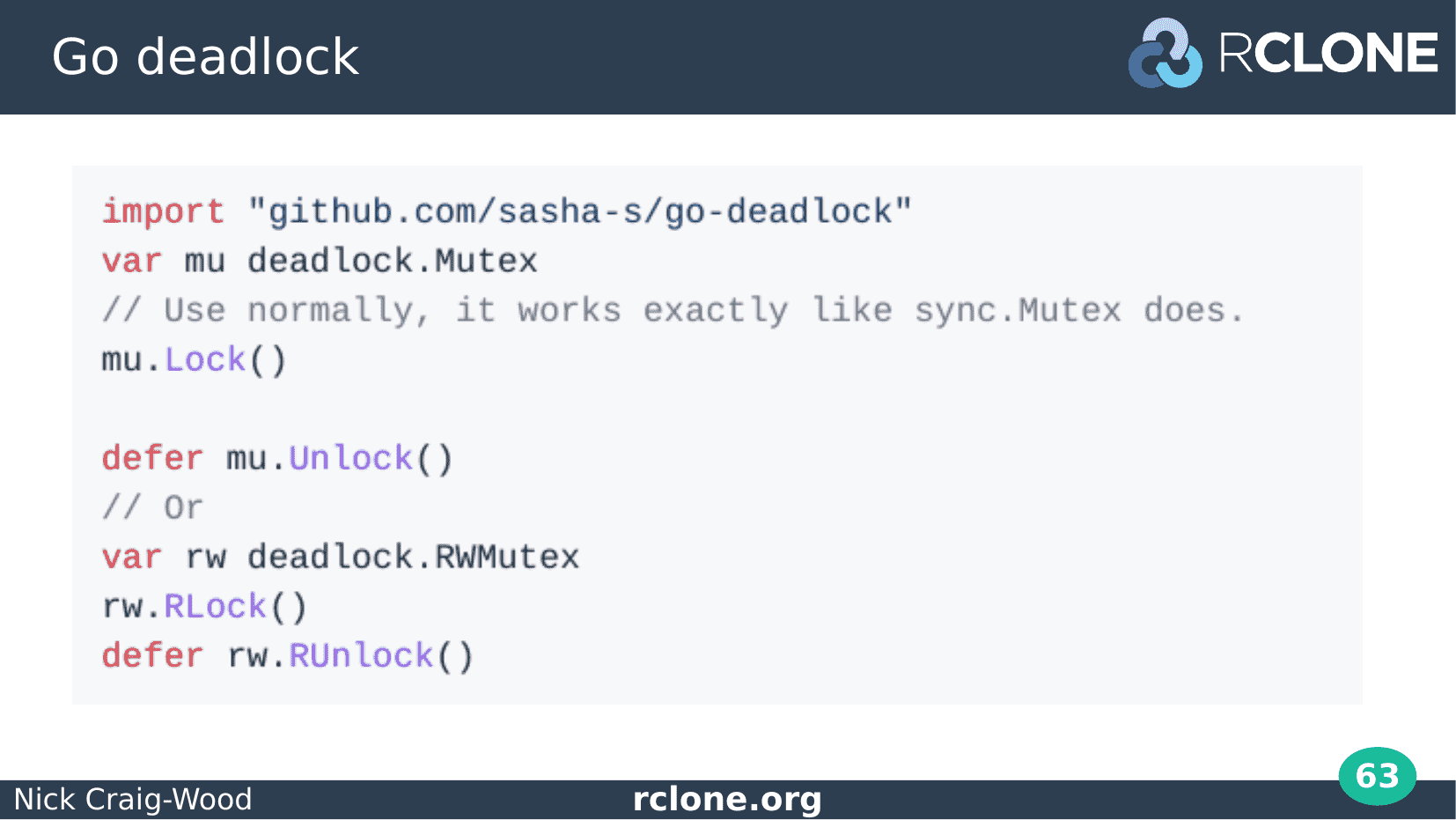

Go deadlock is very easy to use. Here’s the example from its GitHub page.

You just replace your sync imports with a go deadlock import and when you run your code it will give total lock ordering errors.

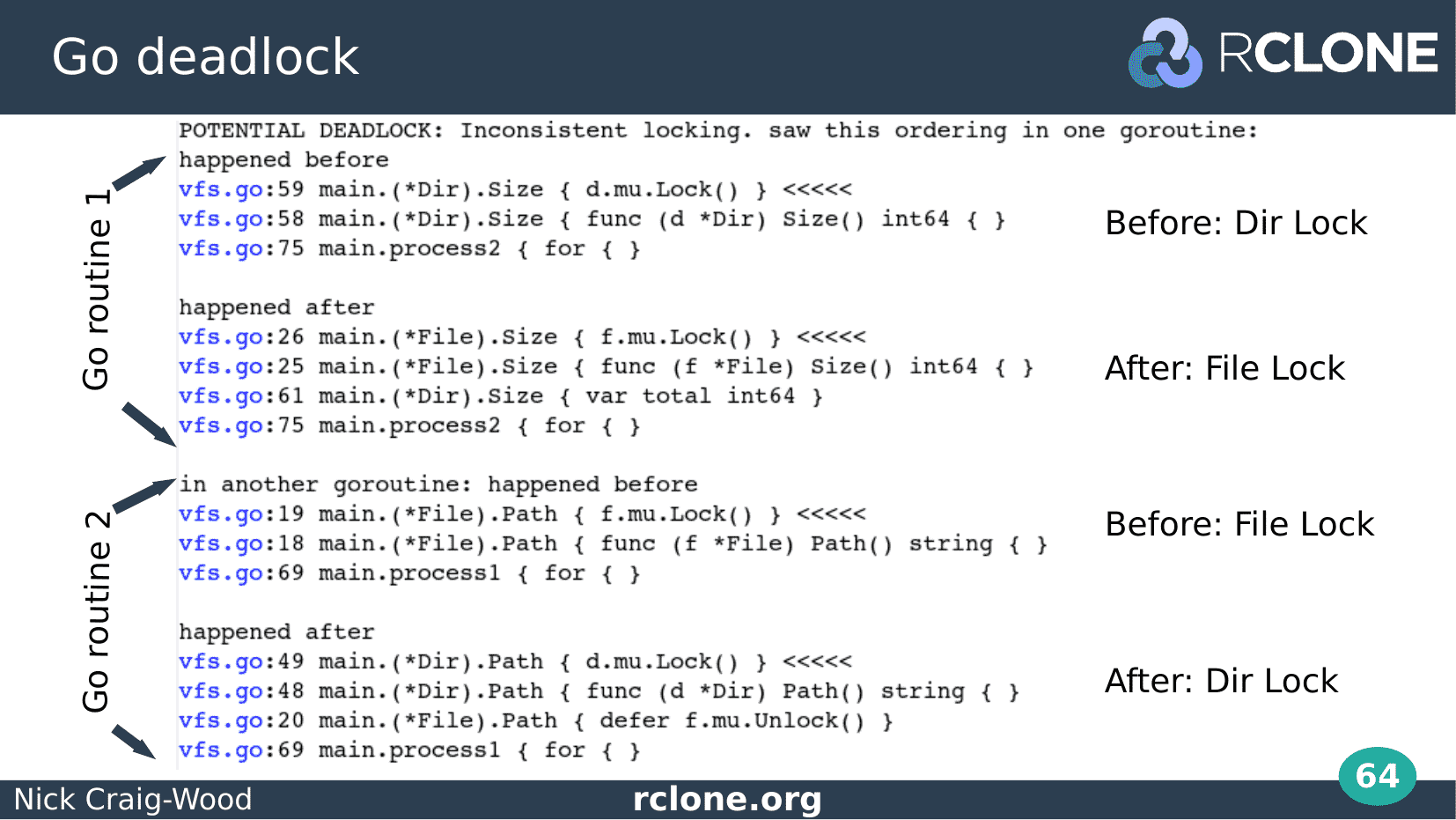

This is what our File and Directory example looks like when run with go deadlock.

As you can see it nicely points out the potential deadlock. The top half is the first go routine and it’s saying the Directory lock then the File lock was taken but in the other go routine (the bottom half) the File lock was taken first, then the Directory lock. It isn’t saying a deadlock happened, it is just saying that because of this ordering of locks a deadlock could happen.

I’ve used go-deadlock on more complicated examples and I have to say I’ve found the output quite difficult to interpret. This is because deadlocks are hard to understand rather than a shortcoming of the tool. So if you do plug go deadlock into your massive concurrent program, expect a bit of head scratching while you work out what the error messages mean!

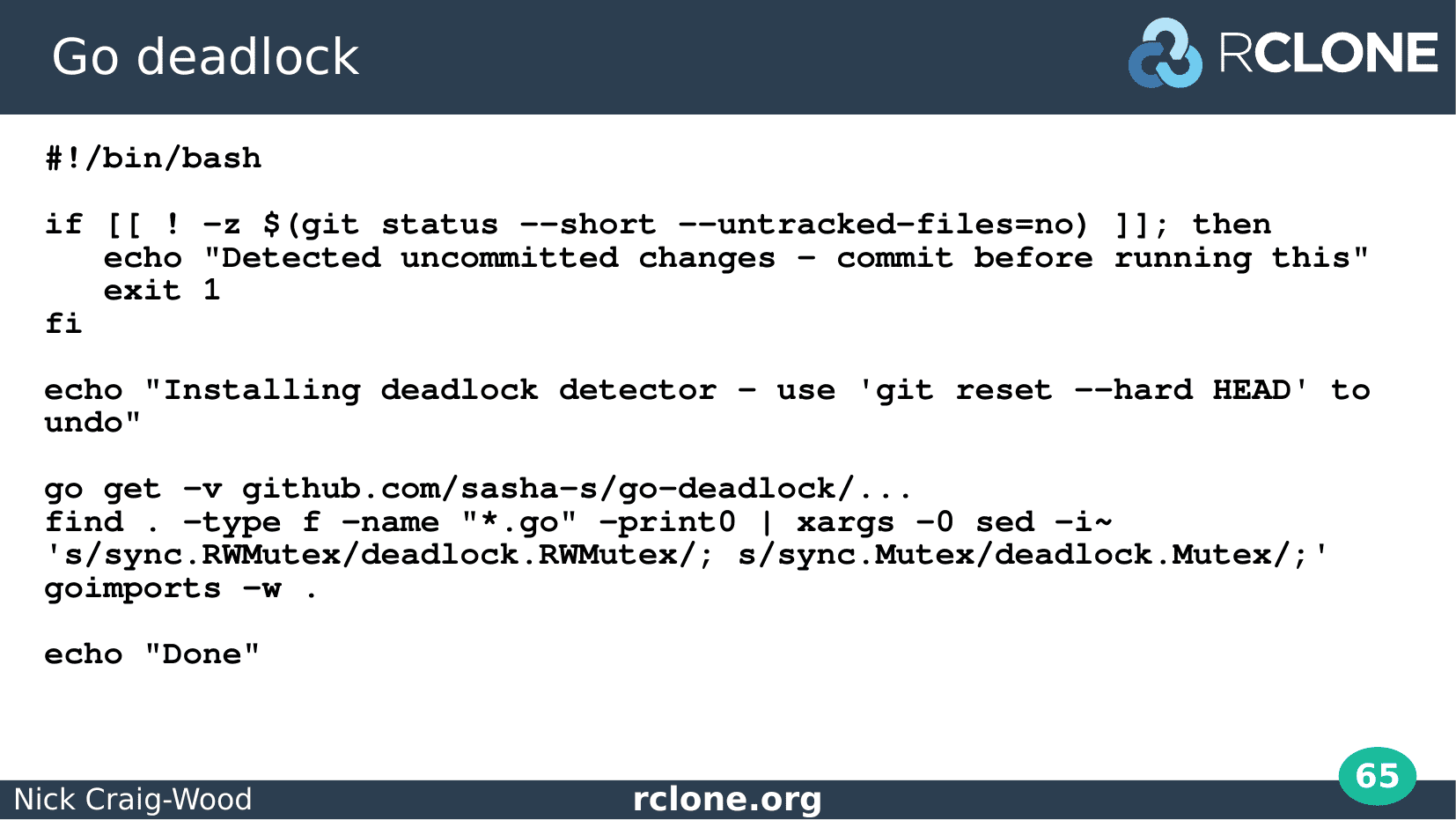

When I want to use go deadlock with rclone I run this little script.

It searches and replaces all the sync Mutex and sync RWMutex with their deadlock detector versions.

Unfortunately I find you can’t leave Go deadlock in production code as it has too much of a performance impact.

I’d like to have a neater way of enabling it for testing, but I haven’t figured that out yet.

Conclusion

This has been quite an intense talk and we’ve gone over a lot of concurrency related things, but I hope you all now have some idea of what a deadlock is, how do debug deadlocks and how to avoid them in the future.

Deadlocks are the curse of concurrent programming, however there good tools for finding and debugging them and there are some promising tools for helping to prevent them happening in any code base.

So if, or rather when, you get to debug your first deadlock, just remember, Don’t Panic, or rather...

...Do panic and collect a backtrace :-)

Thank you all very much for listening.